It is often claimed Robert Browning came up with the idea the area he lived in should be known as Little Venice. At no time did he ever claim any notion of this nor did he write anything that indicated this should be the case.

So who was it responsible for naming this part of Paddington ‘Little Venice?’ Any poet that needs credit should be none other than Lord Byron. But was it really him who named the place ‘Little Venice?’ Its a bit more complicated than that!

Canals were to say the least, smoky and polluted. They were filthy, they stank, and they also doubled as an exceedingly popular repository for dead animals and dead humans – and that often after meeting a most gruesome end. The clanging of metal chains and irons, and horses’ hooves clip clopping were a constant source of noise whilst the bargees shouted and swore endlessly as they loaded up their barges.

The authorities just wanted to get rid of the damn canals. The Greater London Council had high hopes these dirty, smelly, waterways of London would eventually form the basis of a new and much needed high speed road network. Ultimately the only bits of this new roads system to be built was the A40 Westway and the Marylebone flyover, as well as the widening Marylebone and Euston Roads and a few other bits here and there as detailed in the Ringways website.

The need for a pious duty?

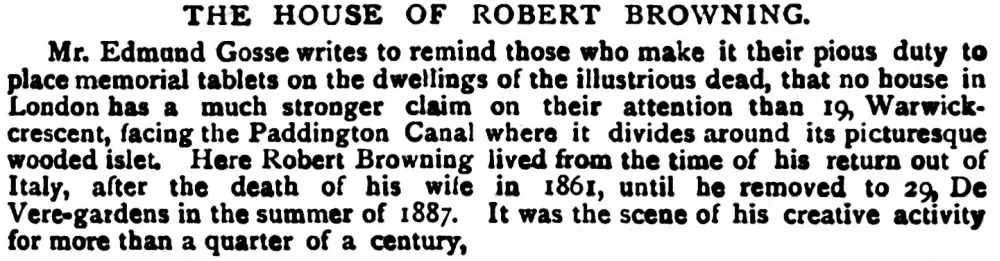

Ought it to be a pious duty to keep things religiously in context? The person mentioned below, a Mr Edmund Gosse of 29 Delamere Terrace, Paddington, had first written to the London Evening Mail with a letter dated 1st January 1890 of the necessity to keep things in proportion. He suggested that out of the many places that ought to be receiving a memorial tablet on the frontage of the house to commemorate its dearly departed famed occupants, one ought to be placed upon that at which Browning had once lived – this being 19 Warwick Crescent, Paddington.

A summarised version of the letter was republished in the St. James Gazette (3 January 1890), again the plea is made for a pious duty to be honoured.

Various versions of the letter were republished in the press throughout Britain during 1890, including the Dundee Evening Telegraph (4 January 1890), and the Sheffield Daily Telegraph (27 August 1890).

The call for a pious duty to be made upon Robert Browning’s house at 19 Warwick Crescent, Paddington. St. James Gazette.

Nowhere in this nor in any other news item covering Robert Browning during the 1850s to 1890 does anyone at anytime call the area anything other than Paddington. Therefore it must certainly be a pious duty to ensure that history is rendered accurately and Robert Browning had at no time ever, contrived to call the locality by any other name than the aforementioned Paddington.

The Borough of Paddington coat of arms which can be seen right in the centre of erm, the Paddington canal locality, is also a reminder the area once went under a different name – even though that borough basically does not exist anymore. Wikipedia.

Clearly a pious duty must be exercised in regards to Robert Browning. As the following will clearly show, Browning had nothing to do with the name of the area where three of London’s waterway routes meet.

Robert Browning and Warwick Gardens

Robert Browning. Source: Wikipedia.

Somehow people seem to have this romantic notion Browning dreamily sat back in his chair at number 19 Warwick Crescent, Paddington, in the mid 1800s, saying to himself, “How lovely are these canals of Paddington, I do wish it was a Little Venice.”

Well if anything, besides the noise and the pollution, boatmen shouting, swearing and quite full of beer I’m quite certain Browning found it at times quite difficult to resist the temptation to give these boatmen a bloody nose, and perhaps even going as far as throwing them the canal!

Fortunately there was a quite tall brick wall which prevented either side getting to blows with the other! Robert Browning HATED Venice! On a visit to Venice (in Italy of course) during 1851, as soon as he arrived he wanted to get out of the damn place as fast as possible! No doubt had Paddington/Upper Westbourne had been called ‘Venice’ in his time he would have hated it too.

That’s because Browning lived in an area known as “the dreary Mesopotamia of Paddington.” Yes! The dreary Paddington Mesopotamia! A land of developing industries stuck between two transport arteries. One was the Great Western Railway the other the Grand Union/Regent’s Canals.

Not one letter penned by Browning has ‘Little Venice’ as an address. They mostly say for example:

19 Warwick Crescent, London. W.

and in others…

19 Warwick Crescent, Upper Westbourne, W.

or…

19 Warwick Crescent, Upper Westbourne Terrace.

Here’s an example similar to the first instance as shown below:

Letter to Tennyson. Source: Bonhams.

There’s this account of a visit to Browning’s London home quite late in the years he lived there. Here’s the text. Nowhere does it say Little Venice. It does mention Paddington and says the area was in fact ‘not particularly pleasant.’

Warwick Crescent “in a locality not particularly pleasant….” this was January 1884.

He died in the real Venice in 1889. Clearly by that time he would have preferred passing away in the famous Italian city with its splendid architecture – a fittingly poetic end rather than an unpoetic death next to a dingy industrial corridor in Paddington.

If Browning was that revered in the area as some claim, why did they call his house (and the others next to it) a ‘slum’ – then proceed to knock down the entire lot? No one was saying in the early sixties ‘Hey let’s keep this house that’s where the guy who invented Little Venice lived.’

Indeed Browning’s house had a plaque affixed to it sometime during 1925-28. It was one of those brown coloured London County Council plaques. Besides Browning’s name it mentioned him as a poet and lived there from 1861-1887. But that’s it! Nothing about Little Venice – because the place didn’t even exist then!

The plaque affixed to the front of Browning’s house in Paddington, London, W2.

They could have done that. Mentioned Browning and Little Venice in unison. They didn’t. Clearly Browning’s name didn’t count in terms of the area – had it in fact been he who had brought to the world London’s Little Venice

As Little Venice rose, Browning’s home was about to fall! Late fifties view before houses demolished. Source: Pinterest.

His home was a notable slum – excess numbers of people lived in squalid conditions in these most disreputable houses which were falling apart at the seams and the council wanted to get shot of them. Practically the entire lot that stood between the Harrow Road bridge and the Westbourne Green bridge (nearly a mile of canalside Victorian housing) was demolished.

Lord Byron‘s ‘Venice’

Lord Byron. Source: British Library.

Lord Byron’s the person to whom we should give thanks for the beginnings of London’s very own Venice. Remember the area’s repute meant it didn’t deserve being known as a Venice of any sort. He pointed out the Venetian canals were just as dirty as those found at Paddington. Byron was merely comparing a number of noted foreign destinations with allegedly similar places that were to be found in England…

This is what he said: “There would be nothing to make the canal of Venice more poetical than that of Paddington, were it not for its artificial adjuncts.”

The whole Byron text re Venice/Paddington is shown below:

Lord Byron’s ‘artificial adjuncts.‘

London’s newspaper The Standard almost got it right below:

Hugh Vickers in the Evening Standard – almost – but not quite right!

Lord Byron was challenging peoples’ romantic notion of Venice by using Paddington’s own dreary waterways as an example. He was saying Venice’s canals were just as dirty as those found in Paddington. Basically he implies if these could be improved, cleaned up, the romantic notion so often chased by many could then be achieved.

It was Paddington long before it was Little Venice

The earliest indications of any notation that the area was likened to Venice were of course made by Lord Byron. In fact by the end of the 19th Century people were acknowledging Byron as the one who had made that very distinction. Browning of course had nothing to do with it.

One of the most noted properties in the area, Beauchamp Lodge, associated with a number of noted personalities, such as Katherine Mansfield (remember this is still the 1920s) and even Napoleon III never ever gave its address as ‘Little Venice.’ It was always 2, Warwick Crescent, Paddington. That’s because this alleged ‘Venice’ in London didn’t even exist!

In fact Little Venice was never thought of until the 1950s. That’s quite a long time after Browning had popped his clogs – thus to even claim that this guy was responsible for re-naming this part of Paddington is nothing more than sheer fantasy!

At no time BEFORE the 1950’s does anyone, or any article (news, letter, book or otherwise) or any photograph or painting say ‘The canal at Little Venice.’ Everyone says ‘The canals at Paddington’ – or – ‘Paddington’s canals.’

For example, Through London By Canal in 1885 is a book that does not mention Little Venice anywhere. It’s all known as Paddington. The canals described are as usual full of filth and muck and not so pleasant to navigate.

The book’s author, Benjamin Martin, clearly acknowledges Byron as a potential originator of London’s ‘Venice’ by way of his adjuncts. This is the earliest acknowledgement that Byron had some notion the canals of Paddington could be a ‘Venice’ if only a few things could change. The person who reviewed Martin’s book agrees that Lord Byron had a strong claim to being the originator of that so called ‘Venice.’

The 20th Century

Early 20th Century view of the pool at Paddington (Kellys.)

As the 20th Century came in, the opening ceremonies of the Blue Lamp or Westbourne Terrace bridge in 1900 and Warwick Avenue bridge in 1907 made it clear the canals were in Paddington and nowhere else, not even Maida Vale. Invariably every single photograph/postcard/publicity of the time and right up to the late forties always alluded to the area as Paddington.

In the 1930’s noted painters like Algernon Newton and Elwin Hawthorne continued to call the area Paddington. Obviously the notion of this place being known as ‘Venice’ had not yet had time to reach the outer periphery of human consciousness. The fact Hawthorne calls it the Regent’s Canal is an example of that. Some called it the Regent Canal, Paddington whilst others called it the Grand Union Canal, Paddington. None of these artists ever used ‘Little Venice’ not ever in a million years.

I thought I'd start today, & this week with Regent's Canal, Paddington by Elwin Hawthorne #painting #ELG pic.twitter.com/Th9AvMXyXX

— EastLondonGroup (@EastLondonGroup) September 28, 2015

By the time commercial boating starts to decline after the second world war, people begin to properly imagine the area being called something other than Paddington.

Some suggested it was like Bruges. There’s a reason. The Belgian city doesn’t have miles and miles of canal. Oh yes it has canals but its not a huge network like Amsterdam or Venice. Its mainly one main canal with some short branches – no complaints it’s very pretty and well worth a visit.

There’s no doubt the second world war had people looking for ways of escapism, of a world that was better without the conflict that raged about everywhere. Many artists lived in the locality thus it was thought the area ought to have a more artistic name.

During that period, this being 1940, it was said this ‘so called Little Venice, perhaps it should be Little Holland – of Maida Vale where the canal is bordered on both sides by residential roads.’ (London Evening News 27 August 1940).

Where in Bruges? Sunday Times August 1945 on the canals of Maida Vale.

So the same for London’s own mini canal network – a bit like Bruges perhaps? But no mention of Little Venice in that article!

Few knew of Bruges so that didn’t work. It probably didn’t even hit international repute until Colin Farrell’s ‘When in Bruges’ hit the cinema screens. Prior to that Van der Valk had been a far bigger thing and that wasn’t even Bruges – or Venice!

Little Venice is born

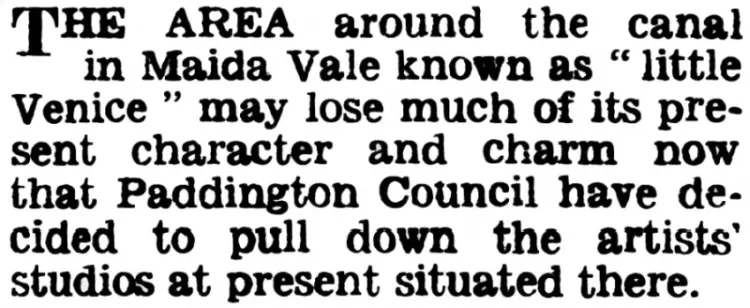

In the 1950s The Metropolitan Borough of Westminster produced a series of publicity material for Beauchamp Lodge events and this is where the term Little Venice definitely originated as an accepted name.

The council hit the nail right on the head. It wasn’t Amsterdam nor Bruges. It was a little sort of Venice. The publicity originally said Beauchamp Lodge was a ‘Little Venetian community centre.’

That slight joke appears to be how Little Venice was properly born.

The council versus Topolski

For some it was no joke. During 1950 it was said the famous artist Feliks Topolski had been very much against the gentrification of the area. Topolski and other artists lived in Warwick Avenue, Topolski at number 3 Warwick Avenue where some of his largest works were undertaken. Topolski was offered a replacement studio on the Embankment where he then worked from around 1954 until his passing in 1989.

The council wanted to purchase his and other buildings for a new public garden overlooking the canal – which would be a sort of late contribution to the Festival 1951 year. Topolski and other artists were very much against the scheme. It was said the houses had extremely spacious rooms in which large artworks could be undertaken. This is certainly true – anyone knowing Beauchamp Lodge before it was unfortunately converted to private residential use would have seen how massive some of the rooms were when it was in use as a community centre.

Topolski and the other artists, one of whom was Sidney Smith and another Marek Żuławski, both then living in adjoining buildings, had formed the Paddington Arts Society and worked together to produce alternative plans for making the area attractive. These plans included a children’s venue, an arts centre, an open air theatre and an exhibition pavilion. These would have all been sited around the canal area provisionally zoned as “Little Venice” and that tied in with the area’s strong artist roots. In September 1950 George Bernard Shaw gave very strong support to this alternative scheme – Shaw was very much against the demolition of the houses because he deemed this would spoil the area’s character.

In one news report a photograph of Topolski’s studio was shown along with a good view of the canal outside his windows. Across the waters could clearly be seen 19 Warwick Crescent where Robert Browning had once lived. No doubt the area’s two most famed properties were ironically spending their final days looking at each other across this expanse of water before the demolition men moved in.

For a long time artists in the Paddington area have found a peculiar attraction in the canal site at Warwick Avenue, in the vicinity of which there are already several studios. Recently they conceived the idea of developing it as a civic centre with studios, gardens, an children’s theatre and exhibition galleries, but the Minister of Town and Country Planning has rejected the proposal. (Birmingham Post 19th September 1950).

All of this was to no avail. Even Harold Mc Millan was enlisted to join the fight. Topolski’s son relates the situation:

He established his first London studio in Little Venice overlooking the Grand Union canal in Paddington a cozy group of four Studios grouped around a central garden he painted there throughout the 40s and entertained… a rich cultural environment… here he threw a party for Picasso who was shunned by the British Elite for his communist stance. Prince Philip was a regular visitor eager to enjoy the delights of Bohemian life. It all came to an end when a local Council jobsworth functionary decided that the studio should be demolished in favour of a public lavatory in a small park. No amount of appeals from the leading figures of the day including Harold McMillan, Lord Eccles and others could change the lumpen planner’s decision… the other three artists were evicted and he (Topolski) became studio less for the next few years. (Daniel Topolski on the life of his father – Youtube).

Discovery of a new place in London no doubt meant a substantial blitz! ‘Little Venice’ to lose its charm after demolition of houses. West London Observer 6 March 1953.

Demolition of the properties began during 1953. There is every indication the name ‘Little Venice’ substantially began life when the artists, including Topolski, had fought to prevent demolition of their houses for what would become Warwick Avenue Gardens. These were renamed Rembrandt Gardens in 1975.

Lord Kinross

One notable local made it clear in a letter to the newspapers during 1966 that it was NOT Browning who had coined the area’s alleged name. This is Lord Kinross and his letter is shown below:

Letter written 1966 by Lord Kinross.

Kinross is correct in saying the Byron had more credibility for the area’s naming, however as the section above shows, that has sometimes been misconstrued.

It has also been argued in some quarters that John Ruskin had come up with the name. One article that tentatively suggests a Ruskin connection can be seen here. No actual reference to any naming by Ruskin can be found, not even in the nation’s newspapers from 1850 to the present day.

Little Venice gains popularity despite road building plans

With an increased fondness for the local waterways, people began to fight plans for a new road network in place of the canals. Sine the 1940s, a motorway had in fact proposed from the Westway right through Little Venice and on the course of the Regent’s Canal. This was envisaged in Sir Patrick Abercrombie’s County of London Plan (1943) and Greater London Plan (1945). This new road would go as far as Camden. Plans for these new roads intensified during the 1950s when it was proposed to extend the new M1 motorway into London itself. The project was envisaged to cost around $30 million.

These plans made the grade during the 1960s under the direction of Transport Minister Ernest Marples when the Westway was conceived. The whole network was intended to be a network connecting the M4 with the M1 and other motorways by way of an inner ring road. The M1 would have in fact reached Marble Arch – and the last junction before the road’s proposed central London terminus would have been an intersection with this inner ring road coming through Little Venice. In later plans the new motorway would have been elevated above the canal rather than built on its course. The plans were modified somewhat by 1969 with the M1 terminating at Kilburn instead and the new ring road heading that way before heading towards Camden where it would follow the Regent’s Canal.

Certainly in 1970 further development of Ringway One (as it was to be known) underwent a planning process. So far the only part of that built had been the section from the Westway to Shepherd’s Bush. In late 1973 the Labour run Greater London Council scrapped the plans for both Ringway 1 and Ringway 2 (including the West Cross and North Cross routes) having previously described these as an ‘urban madness.’ This finally lifted the blight for the many areas faced with having a monstrous new motorway built through their neighbourhoods.

Other schemes too involved British Waterways Board’s desire to sell off its vast Paddington basin for development. Once filled in it would constitute a huge expanse of prime land. Clearly Londoners had by now decided those precious canals were not to be got rid of. Not only that, British Waterways wanted to build an island of flats in the pool area as well as another lot suspended over the canal in Blomfield Road. These would be suspended on silts. Maybe British Waterways had got the idea from the Maunsell forts sited in the middle of the Thames Estuary!

Along with those efforts to keep the waterways out of the grasp of the canals hating authorities and their road building mentality besides the British Waterways Board’s desperate property development plans – evidently whether it was an infill or a series of suspended flats above the canal, there’s no doubt the locals were fed up with what were attempts to change the area beyond recognition.

Thus Little Venice became a place that was to be one where development would not be allowed – even though the Westway had already been built and its ugly face could be seen from the famous pool area, not forgetting the new development which had been built where Robert Browning’s house had once stood. Indeed by the time a sea change occurred, nearly all of the splendid Victorian housing between Harrow Road and Delamere Terrance had been demolished.

Despite this quite substantial blitz – no less than a battle that had began as soon as ‘Little Venice’ had become popular on the tongue, the tourists came flooding in. Trip boats began running through the tunnels to the Zoo and Camden. Towpaths were improved and walking promoted. The area’s famous boat shows began here during the late fifties and ran every year until the early 1970s.

Lord Viscount St Davids was one of the early pioneers (aka ‘the canal peer’) who took advantage of this new breath of life into London’s canals. He started the area’s very first boat trips. Soon John James with ‘Jasons’ came onto the scene too and in due course the British Waterways Board too muscled in on this new found business venture with its distinctive blue and cream coloured waterbuses.

British Waterways’ waterbus ‘Water Nymph’ at Little Venice in 1959. Source: Youtube.

The area that was once Paddington had now developed it’s own identity. Some claim its part of Maida Vale. As Maida Vale was a secession of the area known as Kilburn Fields, so Little Venice’s a secession from Paddington. Little Venice has never been part of Maida Vale. Its an area in its own right and so should really not be attributed either to Maida Vale or Paddington. Ward boundaries were changed to reflect this.

Epilogue

Historically the only person who can be credited with attributing ‘Venice’ to the waterways of Paddington is Lord Byron and even that was not meant in the way Byron intended, eg, to say this area should be called Little Venice.

Evidently it is impossible for Browning to have ever used the name, Venice or Little Venice for the area because even in the latter half of the 19th Century and first half of the 20th Century, there is absolutely nobody (not even Browning himself) who called the area by anything else other than Paddington or Upper Westbourne.

No doubt the area’s wide expanse of water that’s touted as Browning’s Pool is a strange choice. It was actually known as The Broad Water. The island (in those days much smaller) was called Paddington Island (or Rat’s Island by some.) As for Browning’s Island, well there’s no building that belonged to Browning that now overlooks it!

People come to the area to see the boats, the water, the wildlife, to enjoy the trip boats and the many photographic opportunities. Browning barely gets a look in. The famed poet contributed hardly anything of note to the area except perhaps a tree or two. His residency in this once dreary Mesopotamia is quite ironically recalled by way of a most grotty memorial built in Warwick Crescent during 1965. This was sometime after his house had been demolished.

Count the numbers in the thousands on the canal towpath and then count the numbers flocking to Browning’s memorial. A far too easy task because very few know that memorial exists and at no time ever does one ever see hordes of visitors flocking around this memorial. During a typical Cavalcade weekend (over three days during the May bank holiday) the visitor count is around 30,000. One could possibly say the total for the year is perhaps eighty thousand or more – as there are other festivities that increase the total easily. The total count for sightseers to that memorial to the poet could well be eight a month for all one knows!

Its indicative of the true sensibilities in regards to Browning’s presence – for he had not in a million years coined the area’s name contrary to what some think!

Updated February 2026.

Leave a Reply