In writing about railways and canal tunnels one might perhaps wonder why railways and canals in general are not the subject of discussion – apart from the Railway and Canal Historical Society who have existed since the 1950s with the aim of bringing history and topics on both together. There’s no doubt railways were substantially employed in the construction of many 20th century canals and also worked alongside the canals as the many wharves and quays built throughout history have shown – but even so there is not much in terms of the actual interaction between railway and canal tunnel – especially from a construction perspective. Admittedly its quite a difficult subject and its only because of research over fifty, sixty years, including the undertaking of a comprehensive thesis on canal tunnels that an overview of both modes and their intermingling can be discussed on London Rail.

In a general sense, many of the modern era canals such as The Manchester Ship Canal, the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, the St. Lawrence Seaway and the waterways to the Great Lakes, they were all built with the help of railways in the early 20th Century – and that because rail transport afforded a means of shifting huge amounts of spoil and materials. Not only that railways continued to be part of these canals long after they had been completed. The Manchester Ship Canal had its own railway systems and locomotives as did the Panama canal, not forgetting the fascinating rack railway systems that can be found at each of the canal’s locks and whose locomotives are designed to tow the ships through the locks. Its a fantastic subject nevertheless it does hours to research – even to catch up with what is the latest on this subject. The volume of writing would no doubt entail a book! In that respect even so little has been done. There’s one book – Harecastle’s canal and railway tunnels – which is a fantastically commendable work – but it doesn’t cover the subject featured in London Rail even because neither of those tunnels (not even the newer 1960s bore) actually have any relation to the other in terms of actual construction or use even though they are strongly related.

Harecastle’s canal and railway tunnels (2019).

Evidently writing about railways AND canal tunnels is a rather more select subject. Its one that hasn’t been written about – at least not in the sense this series of articles is doing. We saw that railways were used in the construction of canal tunnels nearly 250 years ago, and in the 20th Century, railways were once again used in the construction of canal tunnels. Not only that they were used to repair or rebuild canal tunnels as we will see later. No doubt some of these examples have been mentioned in passing but not as a subject in itself. As for ‘canal tunnel’ as the next section shows, even that can be subject to definition in terms of the world’s biggest waterway systems such as the Panama canal.

Nevertheless there were various forms of ‘tunnel’ on the canals, from drainage adits to culverts and pipes, all of which had the role of either draining away water, of supplying a canal, or enabling water to pass from lock to lock and so on. And in defining a canal tunnel, even the old drainage adits or soughs found in some mines in the Peak District, Lancashire (not forgetting Worsley), the North Pennines, were also canal tunnels of a sort because they had boats as the major transport but even used railways too as part of the mine’s overall transport needs. Some of these, like the Nent Force level have been written about. These again, are another variation on the subject, yet the purpose of this particular series on London Rail is about those canal tunnels that form part of a through waterway, and were either built with the aid of a railway or had a railway laid through it at some later date – and in a couple of examples built because of the railways.

Compared to the railways even, canals are far bigger than their construction implies and this is because a tunnel for example, the air space is simply what can be considered the upper half of the tunnel, the other half being the water the canal conveys. This is why in some instances it was quite easy to convert a canal tunnel to a railway tunnel – because the greater height needed for the trains was already there. What one sees above the waterline is only half the story.

The same can be said for the locks. Locks look quite big but its not until these are drained and one sees the fullest extent of the construction that one gets to appreciate just how huge these structures are. Take the staircase locks on Britain’s canals for example such as Bascote on the Grand Union or Neptune’s on the Caledonian. And even these all have tunnels. Not navigable ones but for the purpose of sending the water through between the various chambers or even side ponds that were used to balance out the locks and obviate the need to dispense of more water than necessary.

A somewhat ‘small’ lock construction from the 18th Century – yet described as a great canal engineering feat when opened in 1774. When one sees the size of the workers in the picture, its clear the scale of the construction was simply gigantic for the mid 18th century. This is the Bingley Five Rise on the Leeds and Liverpool canal. BBC.

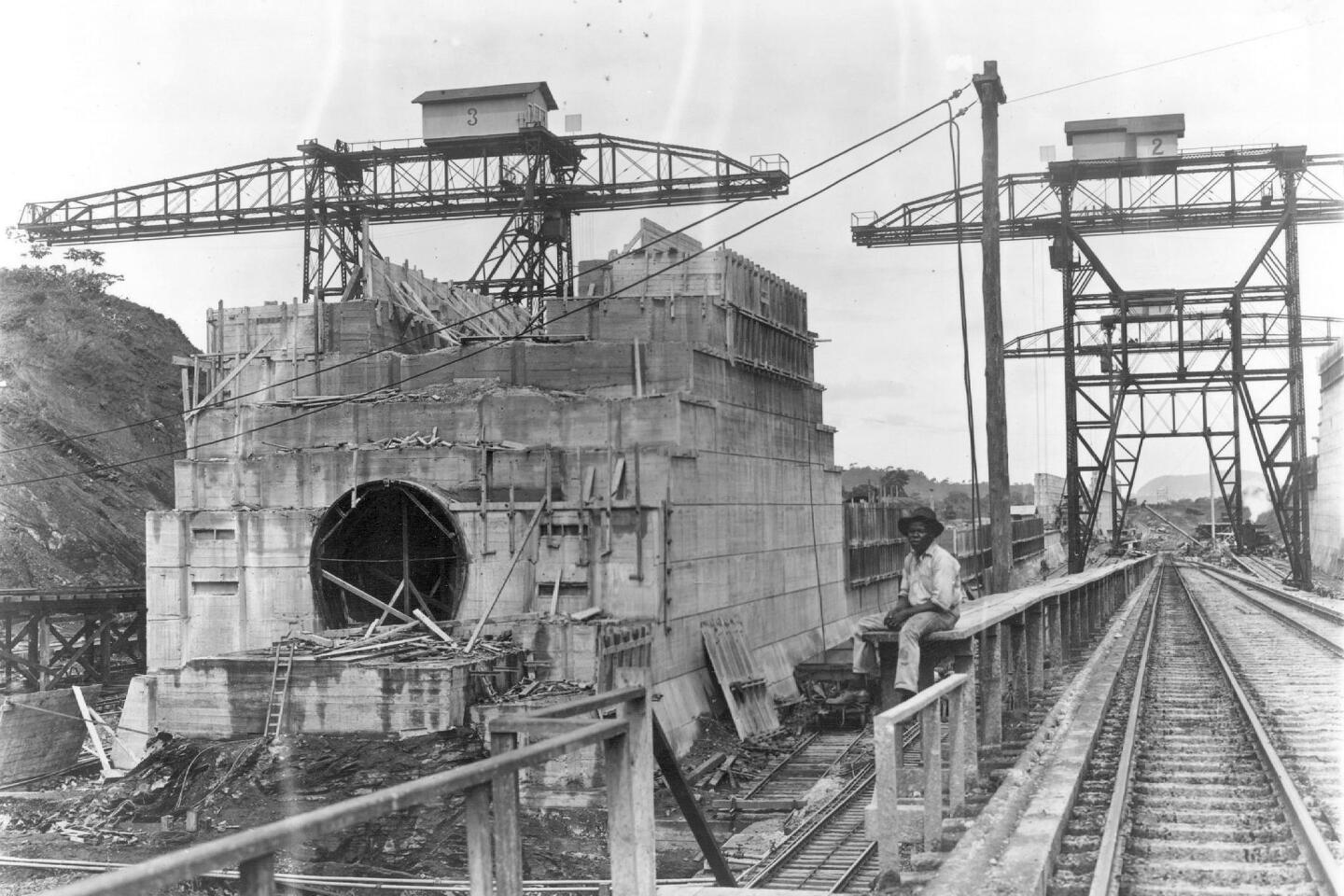

Thus in the sense of diverting or sluicing water between the various lock chambers, there’s one other example of what can be termed an intermingling of rail and canal, and this is the Panama canal with its massive tunnels that were built between the various locks and these had railways running through – both in the form of being built by rail and also in conveying materials for further construction and so on. These tunnels didn’t have boats in them of course – and they never will – but they are used for the purpose of affording shipping a navigation across the Isthmus of Panama, so its another example of the intermingling of the two transport systems, and its more of an indication of how the railways and the canals worked together – rather than being exactly about a canal tunnel itself – nevertheless its an interesting side adjunct to the series!

1910-1914: Pananma Canal

If one translates the Bingley five rise (or the similarly numbered Bingley three rise flight nearby) into say the Panama’s Gatun locks which too has three staircase locks, the difference in scale and height is incredible. Indeed its said nothing on the scale of the Panama canal had been attempted before. As Wikipedia says, ‘the locks were one of the greatest engineering works ever to be undertaken when they opened in 1914’.

The beginnings of a ‘canal tunnel’ can be see at Petro Miguel locks during building of the Panama canal. As the picture shows, the railways were the main enabler of the works (not forgetting the men who did the actual physical work). The various lines allowed so much spoil to be excavated and removed rapidly and materials for construction to be moved in. Both broad gauge and narrow gauge lines were employed. Los Angeles Times.

In a sense one can write about the Panama in terms of ‘canal tunnels’ – and this is because it did have huge tunnels – not for ships of course but for enabling the water to flow between the various lock chambers. The proper name for these would be large culverts but they were technically tunnels – and they were big enough to have railways run through them!

One of those culverts (or tunnels) seen close up. The diameter is eighteen foot. A railway has been laid through the tunnel to facilitate construction. Image adapted from one found on Ebay and colourised by the author.

The building of these tunnels (like everything else on the Panama canal) required the use of a railway to enable their construction. A search for examples of this brought up very little result however one example was found on Ebay (and the result is shown above) which depicts the sort of arrangement being discussed. Ultimately these tunnels were lined with steel and that is because they had to be made completely watertight.

Illustration showing the size of the Panama canal culverts. Wikipedia.

What is interesting is the diagrams of the culverts of the Panama canal (as shown above) depict a railway engine inside. Not that any trains were actually used when the locks were filled with water. But the idea is to show how big these tunnels are. Basically they are in a sense, a canal tunnel! And they were tunnels that actually had railways run through them. Note in the above diagram how illustrations of a six storey building and a horse and cart have been used to show the relevant sizes of the smaller culverts and the general size of the lock chambers (although it must be said the drop between the lock chambers was more like a twelve, maybe even a fifteen storey, building)!

These days the Panama canal has additional locks at Cocoli (east side) and Agua Clara (west side) these are far bigger than the original ones, each group having three locks apiece and these convey larger ships in double quick time through the canal. Instead of using the classic electric mule towing system the new (2016) locks rely on tugs.

In a sense its imperative to mention these things because there is a relevancy especially in terms of what will be discussed in part later – which is that railways were also used to tow barges through canal tunnels! The idea that barges (or ships) need specialist vessels (tugs for example) to tow on sections of canal or through tunnels. Railways were no doubt ideal for that job too and that was because the rails would follow the edge of the canal faithfully. A narrow gauge railway was most ideal because these would fit within the towpaths and the small size of the locomotives meant they could be used in the tunnels without much ado.

In specific situations a railway can do a better job than a tug – and that is because a locomotive (or electric mule) isn’t subject to the vagaries of water currents or strong gusts of wind. Even so, tugs still have an advantage that they have greater flexibility because they can go where the trains can’t! The pros and cons of each would depend on the location in question and the advantages one system could offer over the other.

Looking at this image showing one of the canal’s rack operated electric locomotives (or ‘mules’ as they were called) even the scale of that doesn’t do justice to the huge tunnels that were built in order to sluice water from the upper to the lower levels of the lock chambers. There would generally be three of these tunnels – two on the outer sides of the locks and one under the centre island of the locks – deep below where this locomotive can be seen. Image adapted from one found on Ebay and colourised.

Panama was one of the first implementations in terms of the use of a railway to assist ships and barges through a waterway. The electric locomotives use a rack based on the Riggenbach system. This incredibly successful means of towing ships meant other canals soon followed suit in using railways to tow their barges through tunnels. As we shall see later, the use of railways to tow barges through canal tunnels was so useful this was then used to tow barges along the sections of canal between the tunnels too!

2-10-0 goods engine towing a barge through the Sip Canal. Danube Culture.

One would think it was solely the narrow gauge railways that had a role in hauling barges. That wasn’t entirely the case. The Panama canal’s railways use a five foot gauge track. As for standard gauge, there was at least one example of that used to haul barges! This was the Iron Gates Towline in Serbia (the former Yugoslavia) pictured above. Despite several incursions in which damage occurred to the line, the railway operated until 1969.

As mentioned earlier, there are very few countries which can sport canal tunnels – especially ones that are extremely long. Both France and the UK have some of the world’s longest canal tunnels. France has a number in use that are of considerable length and these are the Riqueval (5670m), Mauvages (4889m), the Balesmes-sur-Marne (4823m) the Ruyaulcourt (4350m) and the Pouilly-en-Auxois (3348m). None of these had any towing railway system and barely any were built with the use of a railway except the Ruyaulcourt.

The Ruyaulcourt is the country’s ‘newest’ having opened in 1965. (Construction actually occurred 1908-1914 when the tunnel was completed – however its entrances were bombed in WWI. These were rebuilt in the 1960s and the middle section was widened to allow the passing of barges). This tunnel is of interest because the period it was originally constructed (the early 20th Century) meant it entailed the use of a railway. Its one of a few in France that were substantially built with the use of a contractors railway.

In terms of construction there isn’t really much to go on with the following examples apart from a few pictures showing a railway in use by the contractors building these tunnels. However what follows is probably sufficient in terms of an overall insight upon the nature of these works.

Leave a Reply