When one thinks of railways and ‘canal tunnels’ one thing would come to mind and its the Canal Tunnels that belong to Thameslink! They are indeed named after the Regent’s Canal beneath which they pass. Its misleading however because they are not strictly a tunnel like that nearby at Islington where the same canal passes through a lengthy subterranean tunnel. Tunnels do usually involve railways but there were some, besides being a true canal tunnel, that had a railway linked to them in one respect or another. In terms of how a railway and a canal could encounter each other in terms of tunnels, well there’s the one example at Edgbaston in Birmingham – and that’s about it really!

Well not exactly! Besides, there’s more to this than meets they eye or even what history has showed. In terms of the UK there’s more to this subject that one would think! Throughout history there have been examples of canal tunnels being assisted in the course of construction (or major engineering repair/refit) by a railway. Indeed it was the construction of a canal tunnel in the 1780s that saw what was likely the world’s first ever contractors’ railway being used to assist in the tunnel’s construction so that’s something that has occurred at least twice before the country’s railways really got off the ground. Not only that the oldest tunnels and bridges on the UK’s rail system predate the Stockton and Darlington railway because those were once part of a canal!

Britain’s canal network was built largely during the canal era – roughly from the 1760s to just before the rail revolution begun and that in turn was part and parcel of the country’s industrial revolution. Anything of a railway nature in those decades were rare, usually it was a situation where a canal would utilise a railway (or rather a plateway or tramway) as a feeder to the canal itself. Examples include the Charnwood Forest or the Ashby canal. South and North Wales had numerous examples and in fact the Penydarren Tramroad, built as a feeder to the Glamorganshire canal, happened to be the world’s first ever railway to feature a steam locomotive – hence Trevithick’s famous locomotive of 1804.

Cuneo’s depiction of Trevithick’s 1804 locomotive. Flickr.

In London there too were examples of this – the best known being the Surrey Iron Railway which was not only a railway in its own right but it was also a feeder to the McMurrays’ canal at Wandsworth. At the other end an additional railway owned by the Croydon canal connected connected its own waterway to the Surrey Iron Railway at Croydon. This was a pure canal railway and its route today is mirrored by a modern railway – the Croydon Tramlink between Reeves Corner and West Croydon station.

Some canals were later bought by the railways and were converted to rail use. As a result some tunnels were also converted to rail use but it of course depended on where. These would be the sort of examples that are being looked for in this article.

Examples such as the Hereford and Gloucester are one example of a canal converted to a railway. It however avoided the canal tunnel at Oxenhall near Ledbury by taking a completely different route to avoid that. The canal is now being restored by enthusiasts who wish to reconvert the railway back to its former use! Another example of sorts would be the tunnels at Harecastle in Staffordshire. The railway followed the Trent and Mersey canal’s example by tunnelling a route on almost the same exact alignment through the same hill. So far so good. However when it came to electrify the line in the sixties, it was decided instead to build a new route that largely avoided the old railway tunnels.

In Scotland two tunnels on the Glasgow, Paisley and Johnstone canal were reduced to mere bridges when this canal was converted to a railway in the 1880s. These examples are of interest but they’re not what this feature is about. The subject is a far closer connection between the canal and the railway – and its often one little known about.

1785 – the world’s first ever contractor’s railway?

What is a surprise is the first instance of a railway inside a canal tunnel came long before railways were really a thing. There is a recognition this may have been the first to be used in a major construction scheme.

This railway was built at Sapperton canal tunnel on the Thames and Severn Canal and it was discussed in some length in a recent (January 2025) West Country Wanderings video. This deems it recent knowledge but it isn’t. Yes Humphrey Household wrote about it in his 2009 book on the Thames and Severn Canal, but Household had also written a much earlier volume under David and Charles and published in 1969. also detailing this unique railway. I in fact referenced Household’s 1969 work in a thesis I was writing in 1970s. The tunnel itself was a vast and dangerous undertaking for the late 18th Century:

The construction of (Sapperton) tunnel was regarded at the time, and has been ever since, as one of the engineering achievements of the day. It took five and a half years to build and extends over two and a quarter miles through the Cotswold hills. Its construction was riven with difficulties but the final achievement is symbolic not only of the energy and enthusiasm of eighteenth-century canal ‘developers’ but also of the construction gangs who risked life and limb (and occasionally lost both) to cut the line through. (Stroudwater & Thames & Severn Canals Towpath Guide, Handford, p98, 1984).

Inside Sapperton tunnel some distance from the Coates portal showing a mix of unlined tunnel with a short intermediate section of both stone and brick work. Hard to believe this water based transit was built nearly 250 years ago with the aid of a railway. Cotswold Canals Trust.

Initial work began at Sapperton in August 1783 to survey the line of the tunnel. During September 1783 various newspapers across the country carried a request for ‘miners and others capable of driving a head-way at the intended tunnell under Sapperton Hill and Haley Wood‘ to apply for work. The text varied slightly between the newspapers. On October 20th 1783 the Reading Mercury announced ‘The tunnel which to join the Thames and Severn Canal, through Sapperton-hill, being near two miles and quarter, is contracted for, and will be begun upon immediately’. The railway did not arrive until a little later. It was built circa April 1785 for Charles Jones, a mason and miner from Manchester, who had the contract for executing the new tunnel. Thus work had been underway at for two years before a railway was even used at Sapperton. Its acknowledged as one of the earliest examples ever of a contractors’ railway. Charles Jones employed the railway to speed up the tunnel’s construction considering the distance one had to get to reach the working face.

Jones wasn’t a very good character though. His workers skimped on the job lining the tunnel in places with one course of brick instead of three as had been stipulated. Jones was dishonest, owed money and failed to pay his men regularly. He was constantly in custody for various matters including binge drinking. This caused the canal company much frustration and in the end they had to get rid of Jones. They gave Jones three months notice in June 1785. The move cost the company an enormous amount of money. The railway was doubtless kept as it was extremely useful.

In any event, three people of worthy importance are known to have visited the tunnel construction works. First was John Byng who is given in some detail below, and then later it was the turn of the King and Queen of Great Britain and Ireland.

John Byng portraiture from 1796 (colourised by the author). Byng was no doubt one of the first ever to write up on a railway being used for a major construction project.

In July 1787 John Byng, the later Viscount Torrington described a trip of around one mile into the bowels of the earth right up to the working face on one of these railway waggons, and he:

return’d to the tunnel mouth… whence a sledge cart issued, drawn by two horses, into which I enter’d, (seated on a cross plank,) for the pleasure of this inspection. Nothing cou’d be more gloomy than thus being dragg’d into the bowels of the earth, rumbling and jumbling thro mud, and over stones, with a small lighted candle in my hand, giving me a sight of the last horse, and sometimes of the arch… – When the last peep of day light vanish’d, I was enveloped in thick smoke arising from the gunpowder of the miners, at whom, after passing by many labourers who work by small candles, I did at last arrive. . . . My cart being reladen with stone, I was hoisted thereon, (feeling an inward desire of return,) and had a worse journey back, as I cou’d scarcely keep my seat.- The return of warmth, and happy day light I hail’d with pleasure, having journey’d a mile of darkness. (Household 1969 p58-59).

Byng reported that about half a mile of tunnel had been dug either side thus from this we know the railway at this time extended no more than half the distance into the tunnel. The mystery is which side of the tunnel did he enter? Household says its Sapperton (eg Daneway) but does not mention how he knows. In fact its Byng who gives a couple of clues (but its not mentioned in Household’s book). First Byng tells us he is just outside Sapperton village and then he is descending a steep path ‘to the intended Saperton navigation; which will join the Severn to the Isis’ (the older name for the upper section of the Thames). Another clue he gives is the tunnel portal is ‘adorn’d by a gothic stone front.’ Hence its easy to deduct the railway used in the tunnel’s construction was projected from the Daneway end.

Another person who possibly saw the Sapperton tunnel railway was King George III. While on a visit to see the Earl of Bathurst, he and the Queen examined the tunnel works on 19th July 1788 and the King ‘expressed the most decided astonishment at a work of such magnitude, expence, and general utility, being conducted by private persons.’ It is said the stretch of canal at Coates is called the King’s Reach because of the visited that was conducted in 1788. It has also been alluded that the King opened the navigation in 1789 (This is rather unlikely as its down to a handful of sources – The Earls of Creation (1962) James Lee Milne being one and The Railway News (December 1908) being another.

The Sapperton canal tunnel railway was no doubt due to the enormous length of the tunnel (2.2 miles or 3.5km) unsurpassed at the time anywhere in the world. Despite the description of a ‘sledge cart’ by John Byng, its clear the trucks had flanged wheels and were running upon wooden rails. The use of iron rails had been possible for nigh on twenty years or more so since the first use of those at Coalbrookdale -however it was probably too early in terms of technological progress for metalled rails to have gained any sort of wider use. Anyway, as Byng’s diary shows, the revelation the railway ran from the Daneway end also gives another possibility – that it began at the nearest road somewhere near to the Daneway Inn.

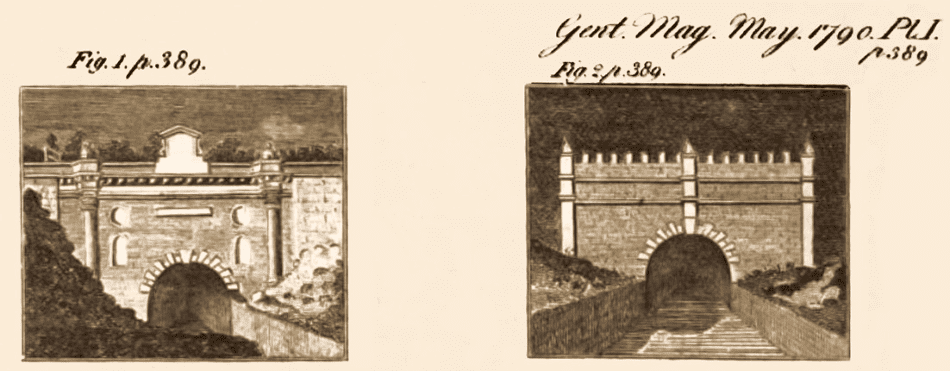

The Thames and Severn Canal Company’s official pictures depicting its two Sapperton tunnel portals. Gentleman’s Magazine May 1790. (Images cleaned up by the author). Google Books.

The tunnel was built by hand but it was certainly was a mega project in those days thus the railway was no doubt valuable in transporting stuff and men to and from the working face and enabling construction process to be sped up. One other aspect not discussed anywhere is that a major advantage of using a railway in the construction of a canal tunnel is it can be used upon a bed that already has a clay lining. Imagine building a tunnel and progressing all the way through and then having to do the whole lot again in order to place a clay lining on the bottom. This is because any transporting and depositing of clay could only be done from one end of the tunnel without damaging what has already been laid. That would be most frustrating and add enormously to the costs of construction. Engineering reports in the author’s possession covering Sapperton tunnel tunnel suggest three quarters of the tunnel had clay lining employed – thus it would have been commodious to put this in place as the tunnel’s completion progressed. This is where the railway then has another advantage and if its built well and the loads are spread evenly the use of it is not damaging any of the newly placed clay lining. No doubt its an absolute necessity especially if its an exceedingly long canal tunnel under construction!

Sapperton tunnel does however shows the use of contractors railways used in the construction of canal tunnels were a rarity and indeed the use that very railway was put to was something practically unheard of at the time. The work was of enormous repute during the closing years of the 18th Century that a ‘tourist’ boat (or a barge suitably prepared for that purpose) was kept at the Coates portal – thus there was no doubt regular sightseeing trips through this stupendous tunnel with its fantastic unlined sections.

Unfortunately Sapperton canal tunnel isn’t a well known example these days in spite of its apparent importance in railway chronology and many will probably know of the adjacent railway tunnel better than the canal tunnel!

1795 – The first half of the UK’s only paired canal/rail tunnels gets built

The Worcester and Birmingham is one of those UK canals that are known for having a number of tunnels including long ones. Work on the canal commenced at the Birmingham end in 1792 and by 1975 it had been opened as far as Selly Oak. This included the 105 yard (96 meter) long Edgbaston tunnel which was the first of five tunnels on the canal as it heads south west from Birmingham towards Worcester. Its one that’s seen every day by thousands who are either walking or cycling on the canal towpath as well as those who frequent the line’s busy train services.

The Edgbaston tunnels in Birmingham. View of the tunnels taken during a boat trip. The canal tunnel has electric lights because the towpath is well used. Author’s photo.

The usual story is wherever a canal is built, a railway usually follows the same route because the canal has already demonstrated an easy and level route through the terrain. That no doubt saved the railway surveyors and engineers a lot of time and expense! The Birmingham West Suburban Railway proposals of the 1870s provided for a new railway to serve the western suburbs of Birmingham and the course of the canal was pretty much that of the new railway too. The railway opened in 1876 as a single track line with passing loops thus the original railway tunnel that paralleled the canal one was of a single track nature too.

In the 1880s it was decided to upgrade the line to double track and straighten out parts of the route. As part of that effort the single track Edgbaston tunnel was enlarged too. The line is now part of the busy electrfied Cross City line between Lichfield, Birmingham New Street and Bromsgrove/Redditch.

A station known as Church Road was opened on the new Birmingham West Suburban line just to the east of the tunnels and its platforms offered a good view of the canal. This station survived doubling of the line and continued in use until 1925 when it was closed through lack of patronage. There is no trace of the station now. However there are two other stations on the line that overlook the canal – University (opened 1978) and Bournville (opened 1876). Rail travellers also get a good view of the canal as their train progresses on the Cross City line.

Both canal and railway tunnel are almost the same length (the rail tunnel is slightly longer as can be seen in the above picture) and these are the only examples in the UK. Author’s photo.

A view of the other end of the tunnels can be seen on Google Streets.

1800 – The Blisworth Hill railway

In terms of the early development of the UK canal system railways were in almost from the very start. Perhaps the biggest example of that would be the Blisworth Hill railway. This was Northamptonshire’s very first railway built to serve the Grand Junction canal while its contractors battled unenviable conditions building a near two mile long tunnel through Blisworth hill. The aim of this tramroad as it was called, was to enable traffic to continue on the canal in view of the construction difficulties deep below ground. The tramroad was built by Benjamin Outram and under the supervision of Pickfords Carrying Company it was operated between 1800 and 1805.

The Blisworth Hill tramway. The perspective looks south from Blisworth village (canal at left) towards the first prominent air shaft in the distance (which can be seen on Google Streets). Image is from a feature on the tunnel and the 1800s tramway at Stoke Bruerne Canal Partnership.

An evocative canal scene from the early 1920s. This shows the Stoke Bruerne entrance to the tunnel. A pair of buttys (unmotorised boats) are waiting for the tug ‘Pilot’ (seen at right) to take them through the tunnel. The butty at front might be a Fellows Morton Clayton. The scene would have been just before the company introduced many new motor boats on its canal carrying routes. Canal World.

As the above picture shows, the smoke from these steam tugs was no doubt problematic. People did suffocate inside these exceedingly long tunnels from smoke emanating from these steam driven barges and that is partially because progress was slow. It wasn’t just that, ventilation too was dire and the canal company were forced to open up some shafts for additional ventilation. It would take rather more than half an hour, even forty minutes, to complete a single transit of the tunnel, whilst a butty that dared to venture through the tunnel on its own (by way of legging – eg pushing along the sides of the tunnel) would take an hour and half or more. Here’s a report from the Northampton Herald for September 1861 on the deleterious effects a steam barge had on its crew – two ended up dead whilst the remainder of the crew were found slumped and totally unconscious.

Stone sleepers and plate rails from the Blisworth Hill line discovered during excavations in the 1960s. Blisworth Website.

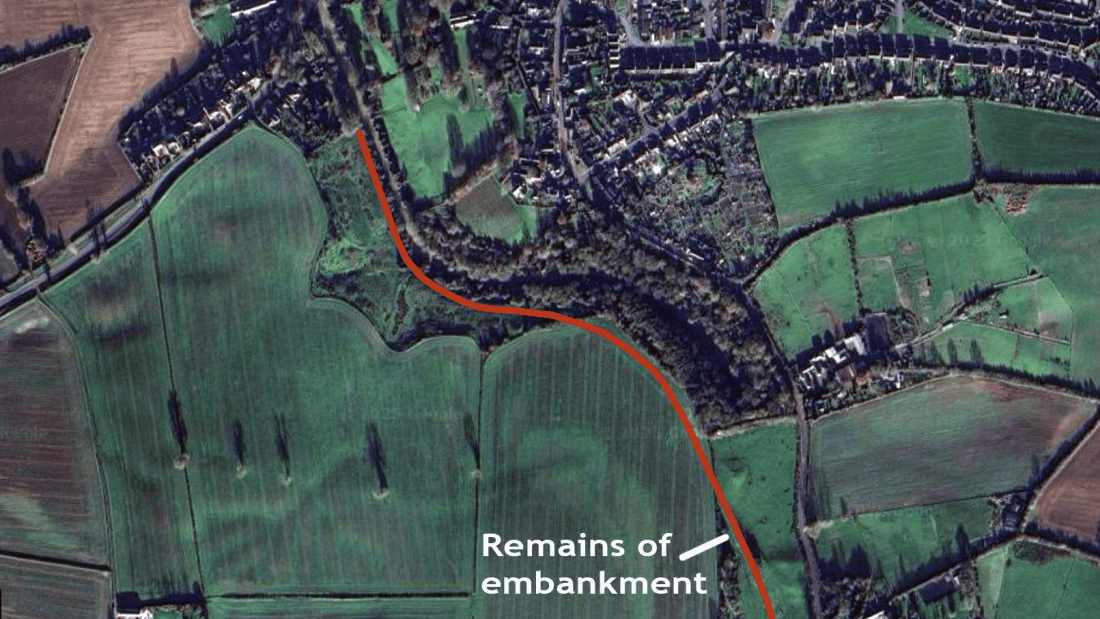

What can be seen of the course today at the Blisworth end (from the village as far as the embankment shown in the next picture) using the aerial view at Google Streets.

The former course of the tramway can be seen in the shape of this remaining bit of embankment heading towards Blisworth. Google Streets.

Its quite hard to find any traces of the Blisworth Hill tramway (apart from the northern end) and that was the case even in the late 1970s when explorations of the area were made. Author’s photograph 26th March 1978.

The above scene from March 1978 taken by the author shows the B class road near Stoke Bruerne and even this is a scene that’s impossible to see today (see Google Streets). The dirt track leading south behind the photographer is part of the former boat horse path. The tramway itself ran across the fields to the right but no trace of that remained even though it had once used a slightly raised embankment. Its course soon took it across the road in the far distance to run behind the air shaft that can be seen and from there its route was basically that as far as the embankment depicted earlier. The trees on the left hide a large mound consisting of spoil from the tunnel whilst the air shaft is the first boats encounter en route through the tunnel from Stoke Bruerne to Blisworth.

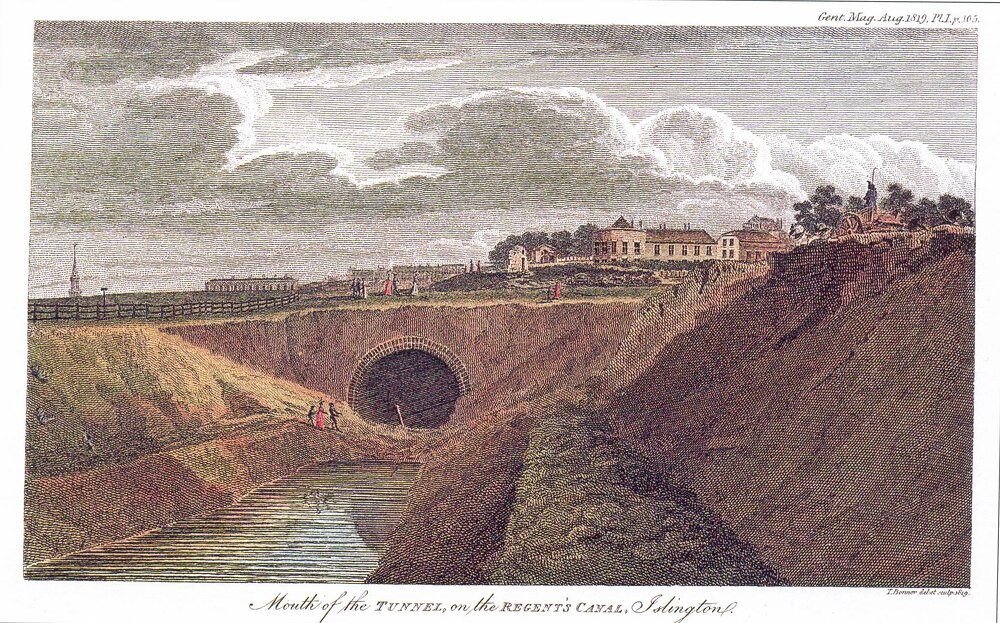

1815 – Contractor’s railway for Islington canal tunnel

The one and only other use of a railway in a canal tunnel was a contractor’s railway at Islington in London. The tunnel was during 1815-1820 as part of the Regent’s Canal from Camden down to the River Thames. In order to speed up the tunnel’s construction somewhat a double track line was progressively laid through the workings and used to convey out spoil as well as bring bricks to the working face in order to complete the tunnel’s arch and invert as construction progressed. Its not known who instigated the railway nor are there any details as to its use. The only knowledge of the railway is a drawing that depicts the tunnel’s construction.

Construction of Islington tunnel. Probably depicts the first phase of construction during 1815. Friends of Regent’s Canal.

Its not known when use of this twin tracked tramway began, but the tunnel was built in two stages between 1814 and 1818. Construction was meant to have begun in the summer of 1814 but there were problems acquiring the land at either end. In the final days of 1814 work finally began. At the end of January 1815 four shafts had been sunk and 140 yards of the tunnel completed. The very limited number of shafts that were built because of securing access to the land above was a possible reason for employing a tramway to help facilitate the works. Also a lengthy cessation of construction between December 1816 and August 1817 possibly urged the use of the tramway in order to speed up work. The tunnel was finished in 1818 but no water was let in until sometime in early 1820.

Images of workers constructing a canal tunnel at any time, let alone in Georgian days, are practically non-existent thus the view of navvies working inside the unfinished Islington tunnel using a basic tramway to convey spoil out and bring bricks to the working areas has to be totally unique!

Picture of the Islington tunnel showing its twin tracked wooden tramway. The image was enhanced and colourised by the author from one found at Friends of Regent’s Canal.

At the very end of the 19th Century there were plans to use the Regent’s canal for a monorail. Plans were deposited in the early 1900s before the Royal Commission on London Traffic but nothing came of Behr’s railway – except for the one railway arch that was built in anticipation of that. This is the empty Great Central railway arch at Lisson Grove (Westminster Extra) which was indeed built for this monorail system to be situated alongside the Regent’s Canal. Islington’s canal tunnel would have a twin pair of tubes driven adjacent to it to accommodate the North Metropolitan and Regent’s Canal monorail system proposed by F. H. Behr. This tunnel was to be 1530 yards against the canal tunnels length of 960 years and because Behr wished to avoid building additional bridges in the cuttings used by the canal on the approach to the tunnel. There was every intention to keep the canal however it would be populated by the monorail line either at its side or suspended above the water in the same fashion as the Schwebebahn at Wuppertal.

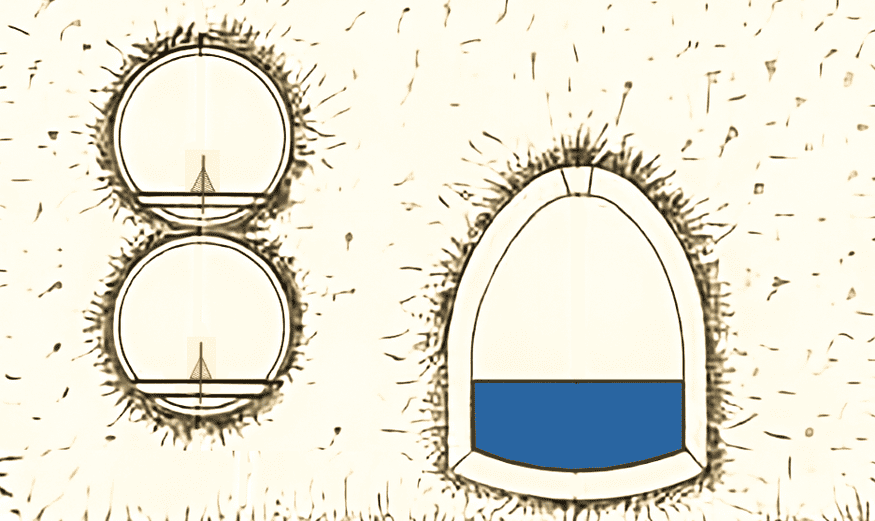

Behr’s plans for a monorail tunnel adjacent to Islington canal tunnel. This was one of three projections – the other two showing the monorail tunnels at an angle and another showing the monorail tunnels level with each other – these being dependent upon the infrastructure at various locations.

1824 – Britain’s oldest working railway tunnel opens!

In this the year 2025 everything is about Railways 200. But what isn’t being said is one of the oldest parts of Britain’s railway system happens to have been built and opened before the Stockton and Darlington railway. Thus its the oldest passenger railway tunnel in the country. And that’s because the tunnel was originally part of a canal!

This was the Strood tunnel on the Thames and Medway canal (opened 1824). This, at 2.2 miles (3.5km) was between Higham and Strood in Kent and an immense tunnel by any UK standards. Thats because it was designed to accommodate sailing barges travelling between the Thames and the Medway rivers. The following is of interest:

The original single tunnel was 4012 yards (3668m) in length and at the time was the second longest in Britain and the largest in terms of volume of excavation. The tunnel had a 5 foot (1.5m) towpath on its northern side with the base of the canal some 11 feet (3.5m) below towpath level lying at about 2.4m AOD. Towpath level is now about 1.8m below track level (Figure 2). The tunnel was designed to take 60 ton sailing barges up to 100 feet (30.5m) long and 18 feet (5.5m) high. The canal was closed for 10 weeks in 1830 so that a 139m long section of tunnel could be opened out in cutting (up to 30m deep) to allow a passing basin to be built. This open section, known as the “Bombhole”, split the tunnel into two sections, the Higham Tunnel being 1529 yards (1400m) long and the Strood Tunnel 1 mile 572 yards (2129m) long. (Geological Society).

Its not known if a railway was used in the construction of Strood tunnel for there’s no record – and that despite the contractors being Pritchard and Hoof of King’s Norton (of which one half of the partnership had been responsible for Islington tunnel) and despite quite detailed accounts of the tunnel’s construction – for example The Public Works of Great Britain by F.W.S. Sims (1838).

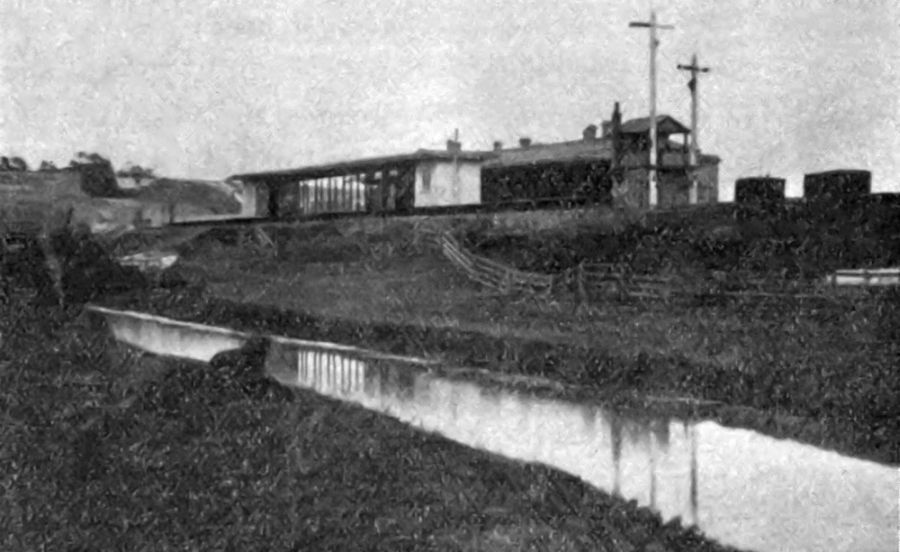

The Strood (or Frindsbury) portal in 1845 showing the railway as it swept round to join the canal through the tunnel. Victorian Web.

Soon after the tunnel was split into two the Gravesend and Rochester railway wished to use the tunnel for their new railway thus an agreement was made that a railway could be upon the tunnel’s wide towpath. The very first train ran through the tunnel on Christmas Day 1844, however public services began at the start of 1845. Very shortly after in 1846 the canal closed and the South Eastern railway (the successors to the previous company) were able to build a proper trackbed formation through the tunnel’s length. If one travels on a train between Higham and Strood stations, they are indeed passing through the oldest tunnels in use on the UK’s railway system!

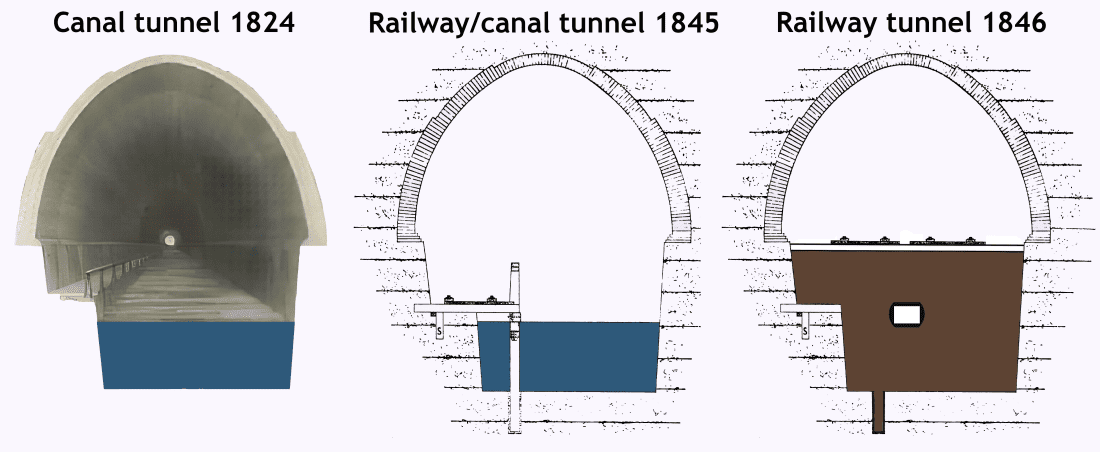

How the Strood & Higham tunnels progressed from canal tunnel to railway tunnel. Diagram created by the author based on two sources at 1) Geological Society and 2) Charles Hadfield The Canals of South and South East England.

One of the earliest railway photographs no doubt! This is Higham station in 1854 with the now truncated Thames and Medway canal in the foreground. Note the slotted signals which were common in the early decades of railways. What is curious is the down platform buildings are of a design almost a century before Britain’s railways even saw this sort of structure used. Clearly someone had been time travelling in order to see what the future held! Internet Archive.

The Thames and Medway canal still exists to this day. About a mile and quarter of it has been restored at Gravesend and this can be easily seen from a train running on the railway between Gravesend and Rochester. Beyond that restored section, the canal’s rather derelict route of around 2 and half miles can be be tracked by train as far as Higham station, just before the railway enters the tunnels. Water that is extracted from the railway tunnels is ironically pumped into the canal which then takes the excess water away to be deposited into the Thames.

Although not technically within the remit of this article, mention must be made of the River Cart aqueduct. Its located in Scotland and its the world’s oldest railway bridge still in use. It was originally a canal aqueduct and opened in 1811. Upon closure of the Glasgow, Paisley and Johnstone canal in 1881, the route was repurposed for the Paisley Canal line and the aqueduct now carries a electrified suburban railway.

Main picture is of the Edgbaston tunnels in 2004. Picture taken by the author.

Updated 15th, 17th, February 2025.