This is part two of the railways and canal tunnels feature. Whilst it was suggested one of the earliest contractors railways had occurred during the mid 1780s as suggested in part one of this feature, the fullest history is incomplete there in terms of railway chronology – and that is because the next railway/canal combo is an even earlier example. There’s no canal tunnel to begin with in this equation – thus the Sapperton example given previously still stands as perhaps the earliest known example of a railway being used in the construction of a canal. Even though the next example is not exactly a pairing of rail and canal in terms of a tunnel, from the very start, a canal tunnel was soon built in order to improve the interchange of goods between both railway and canal.

The tunnel in question was one of the smallest and tightest in the entire UK canal system and in order to connect to the railways on the other side of the tunnel boats had to use this very diminutive tunnel. The history of this amazing railway/canal interchange starts from the early days of the canal right up to to the second decade of the 20th century however just a short part of that history is discussed here.

1778-1920: the Caldon Canal and railways at Froghall

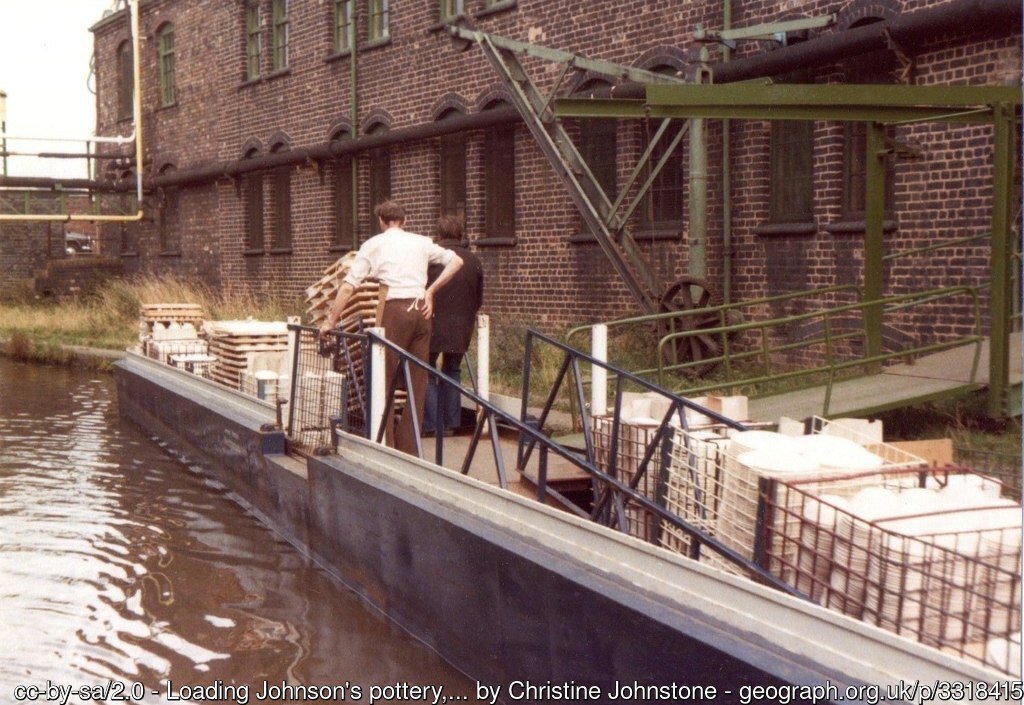

The Caldon canal is a branch of the main Trent and Mersey canal at Stoke on Trent. Both waterways were surveyed and engineered by James Brindley. The Caldon canal is unique that it was a waterway that continued to operate commercially long after most of the country’s canal system had lost its canal carrying traffic.

As the above photograph shows, this commercial traffic operated until 1986 because the canal was the best way to transport vast quantities of pottery intact between the Johnson Brothers’ factories. This traffic used four miles of the canal at its Stoke on Trent end between Hanley and Milton. Geograph.

For the purposes of our railway/canal tunnel feature we must however go to the country end of the canal which was at Froghall, some fourteen miles further east. The canal once went as far as Uttoxeter, however that route was later converted to a railway. There was a canal tunnel on that part of the route at Alton, however the railway decided to avoid this by way of a deviation using a cutting instead.

The main reason for the construction of the canal was to serve the quarries at Cauldon Low. Froghall was no doubt the nearest the waterway could get because of the nature of the hilly country. To complete the connections a tramway was built and this is perhaps the earliest use of such a railway as part of a canal system.

This excellent view of the steeply sided Churnet valley shows the canal on its approach to Froghall. The old wharves were this side of the hill seen in the distance. The new wharves & railway interchanges were on the other side of that hill. One can easily see why a canal tunnel was needed for the extension. The attractive canal side property seen in the picture is for sale in case anyone’s wondering! Denise White Estate Agents.

As for the canal tunnel that is the subject in question, it wasn’t built until a few years later – and that only because a better site was needed for the intersection of both canal and railway. That site happened to be on the other side of the hill compared to the earlier site, and that is why a canal tunnel was built. The tunnel could have been avoided but not without difficulty because the sides of the valley were already quite steep and building the canal on the contours around the hillside would have required more work. Thus the tunnel was essentially the easier option.

Its because of this the huge interchange between canal and railway (and the local roads) came in to existence. The canal’s original terminus some 500 metres west wasn’t suitable for for a development as extensive as that which eventually came into use at Froghall. The original terminus offered a poor starting point for the onward tramway of 1778 to the nearby quarries because it was the steep sides valley (plus a poor grasp of the engineering involved) that resulted in a less than efficient canal interchange terminus and a tramway that was built very poorly.

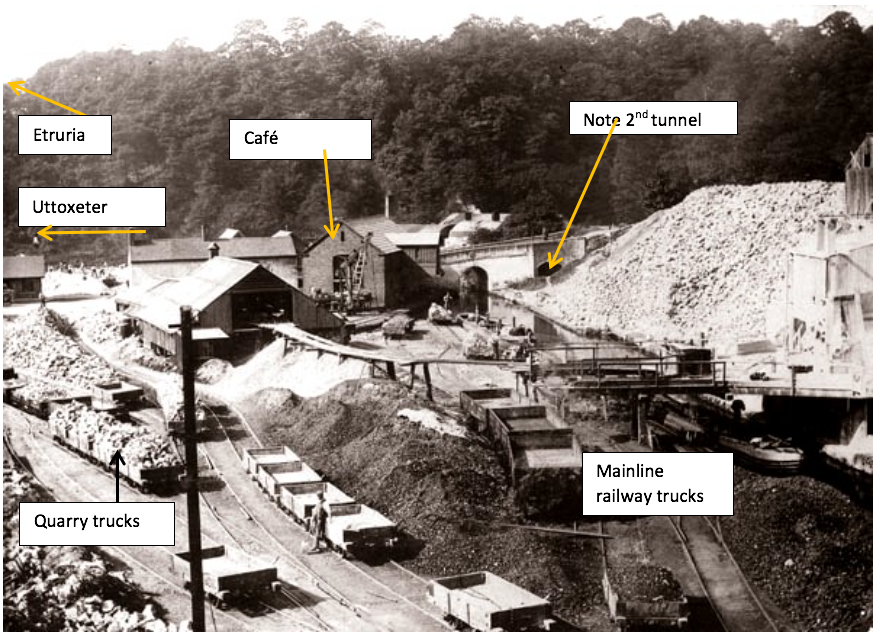

The Caldon canal at Froghall (the iconic canal warehouses are now ‘the cafe’ as denoted above). Compare this with the author’s photograph (shown below) taken some seventy or eighty years later. National Transport Trust. To compare with the above, the current site at Froghall can be seen on Google Streets.

By building an extension to the canal (including the tunnel) the whole job of both canal and tramways/railways working as a complete whole was made much easier. This improvement began to see results some ten years after the canal had originally opened.

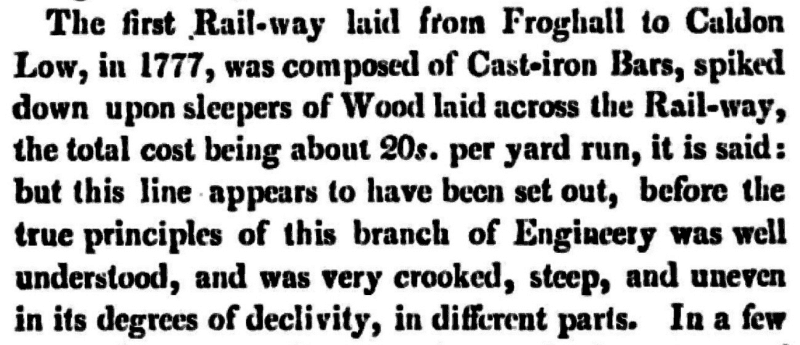

In terms of canal history, the use of railways at this very early stage is amazing. No less than nine years after the opening of the Bridgewater canal, the Caldon canal had opened and it was employing a railway to further facilitate its business. The first of those railways opened in December 1778 (or maybe earlier if the text shown below is anything to go by) and it used a mix of wood and iron rails from the start. What that means is the main part of the rail consisted of wood however the top most part upon which the wheel ran, was of iron plate. This railway connected to the canal at its original terminus which was just a short distance west of the tunnel.

The suitability of the track (whether it would be wood or iron – or even both) was probably due to the local connectivity each element of the process had at the time. In the industrial Midlands or northern England (or in this particular case) the Potteries, there would be every likelihood a new railway or tramway would have used iron rails of some sort whereas in places like the Cotswolds (Sapperton tunnel) or London (Islington tunnel) wooden trackways would have been the modus because wood was easily procured.

The Cauldon Low tramways as described in General View of the Agriculture of Derbyshire Volume 3 (1817). Google Books.

What that means is in spite of the canals using iron from the very start – including the quoins for the locks, the winding gear for the paddles and other instances, the canals used wood as much as possible and iron as little as possible because of the costs of manufacturing and transporting the iron. Evidently the closer a canal was to a centre of industrial production, the greater the amount of iron that could be used. For something like the Pontcysyllte aqueduct, the construction of this stupendous structure was possible only because one of the ironworks used to manufacture the vast quantities of iron needed was just down the road. In terms of the Caldon canal’s early tramroads, a compromise was made where wooden rails were used with cast iron bars on the top, which shows it was possible to transport iron from the main industrial areas around Stoke on Trent, but the remoteness of the valleys hereabouts still placed limits on the amount of iron that could be transported thus wood was used for the main part of the rail formation.

The amount of iron being conveyed would not be a lot thus during the construction of a canal, a single cart could quite easily have delivered all the iron ware needed to build perhaps a couple of locks or some other structure. Iron rail for the purpose of a tramway was a different matter however. It all depended on where the iron was produced. Once a canal had been finished, any connecting railways would have found it more prodigious to use iron rails because the narrowboats could easily transport tonnages far in excess of anything the horse drawn cart could. Its interesting the early tramways from the canal to the Cauldon Low quarries used both wood and iron which was no doubt a compromise at the time in terms of the expense of manufacturing and transporting the iron. Such intricacies didn’t matter when it came to building the later tramways which would link the canal and quarries because the costs had by then dropped considerably and vast tonnages of iron rail could be conveyed without much bother.

Picture of Froghall wharf in June 1977. Photo by the author.

The derelict look here at Froghall lasted a fair few years after the canal had reopened in 1974 and was much the same when the author took the above photograph in 1977. This part of the waterway was seldom visited by boats due to the constraints of the canal tunnel itself. The following year Froghall wharf was reached by boat with the author and others. That was at the end of May 1978 – and the same exact air of dereliction existed here as it had a year earlier when the author visited the location by car. The derelict buildings seen in the 1977 picture are now a cafe and shop as shown on Google Streets.

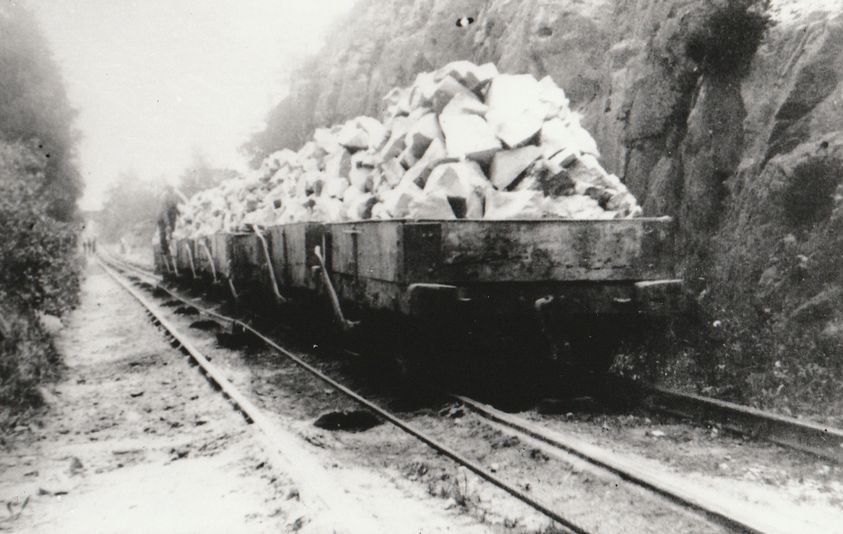

The later inclined railway which lifted the line from Froghall wharf to the Cauldon Low quarries. Facebook.

By 1802 the area’s tramways had been upgraded and inclined planes were provided – and these were designed by the engineer John Rennie. A tunnel for the tramway was later built and its is known as Trubshaw’s tunnel (after the engineer of the same name). Speaking of tunnels, the fact the canal tunnel at Froghall even exists is because it was part of that wholesale improvement. The canal was extended via this new tunnel to a location more suited to that previously where the canal had ended and the original 1778 tramway had commenced its journey to the quarries. The new Froghall wharf was a place where all the tramways and railways could better be serviced and more easily be able to connect up with the canal itself. In its heyday Froghall was a most impressive site with all manner of canal and railway operations – including inclined planes that led straight out of the wharf area and up the hills towards the quarries.

The construction of the new railway system was no doubt helped by the ironworks that had by this time sprouted up in the area and in turn helped by the new limekilns at Consall Forge a little further up the canal. Today the forge is a listed structure.

Boat entering the 4′ 4″ (1.34m) high tunnel in 1981. The headroom in the tunnel has been slightly more generous (5 ft or 1.5m) since 2003 when the level of the canal was dropped somewhat. It still precludes a considerable number of boats getting through however. Wikipedia.

There is one question however. Why was such a diminutive tunnel was built – especially if boats can’t get through it? Well that is a problem for the leisure canal boats that operate today, but it wasn’t a problem for the work boats in the past. The first point of note is the construction of such a tunnel was because it was cheaper and the traffic that would use it wasn’t really ever going to change. Most of the canal traffic to Froghall entailed laden boats in either direction – thus pretty much every boat that traversed the tunnel would have been low down in the water anyway – so the height of the tunnel wasn’t a problem.

In the outward direction (from the mines around the Potteries) boats carried coal for the quarries whilst in the other direction (eg towards Stoke on Trent or other areas of the Potteries) boats conveyed excavated material from the quarries. Thus the tunnel’s constraints wasn’t injurious to commercial boat traffic. But for those leisure boats that might be able to get through, its an extremely tight squeeze as this Youtube video shows!

The new canal tunnel which was opened c1786, therefore had the unique situation of being built in order to facilitate a better intermingling of both canal and railway system. It was no doubt a different example to the others so far written about – its the only canal tunnel in the UK whose purpose was to maximise its onward rail connections.

These canal oriented railways developed quite exquisite systems and that to Cauldon Low had its own tunnels too. Not forgetting these splendid locomotives that were basically the standard gauge’s bigger brothers of the highly venerated Welsh quarry locomotives. Facebook.

After the 1920s traffic declined via the tramways and canal at Froghall, the Cauldon Low quarries continued to thrive because these had a more effective connection to the outside world via the North Staffordshire Railway to Leekbrook Junction where it connected to the main UK rail system. Despite eventual closure of that too, a substantial part of the system hereabouts has been preserved and is these days known as the picturesque Churnet Valley Railway.

Thus on sections of the line there is a very interesting intermingling of both canal and railway – Consall station (just a short distance from picturesque Consall Forge) is located in a beautiful but steep sided and narrow valley however space was at such a premium the railway builders had no option but to build the station’s platform and small waiting room suspended over the canal!

The Churnet Valley’s Consall station platforms and waiting room are suspended over the canal which is indeed very narrow – its channel is barely wide enough for one boat! Voyages of Gabriel.

The old photographs seen above (as well as others) can also be seen in canal books such as Historic Waterways Scenes – the Trent and Mersey Canal by Peter Lead (1980) which has a vast depository of old canal and railway views of the entire canal between Etruria and Froghall.

1790 to now: Hardham Tunnel Sussex

This is an unusual one. Its a sort of in-between – a canal tunnel but its not part of a canal system. Not only that, a former boating tunnel which concerns the main railway system to this day. The tunnel is the UK’s only example to be found on a river navigation. This is the River Arun which linked up other local waterways including the Rother navigation, the Petworth canal and the Wey and Arun canal.

The reason for the tunnel was the Arun took a lengthy loop of about three miles. The shortcut via the tunnel was much less than a mile, thus a considerable saving in transit time was achieved especially if the barges concerned were working against the flow of the river.

The railway involved was the former London Brighton and South Coast company who built the line between Horsham, Arundel and the south coast. The new railway line entailed a number of crossings of the River Arun and even in places the river was diverted to make way for the line. However the Hardham tunnel was part of an active waterway at the time of the line’s construction – thus it wasn’t possible to make changes like those that had been done elsewhere further south.

The tunnel’s presence is not urgent as it seems quite stable and there has never been (to my knowledge) any problems that have arisen. Nevertheless Network Rail are able to inspect the tunnel whenever it is desired. This is possible because of work which was done eighty or so years ago by the Southern Railway.

The rather fragile north portal of Hardham tunnel. Youtube.

The location of the tunnel is just to the south of what was once Hardham junction and the diverging line to Midhurst (see Google Streets). The bargemasters going through the tunnel – and even the visiting boats – had to either leg or pole their vessel’s progress whilst any horses would have been taken over the top. When the railway was built a footbridge was provided for the boat horses to continue their journey uninterrupted. A modern replacement footbridge exists at the site (see Google Streets) and can be found a short distance from the former junction.

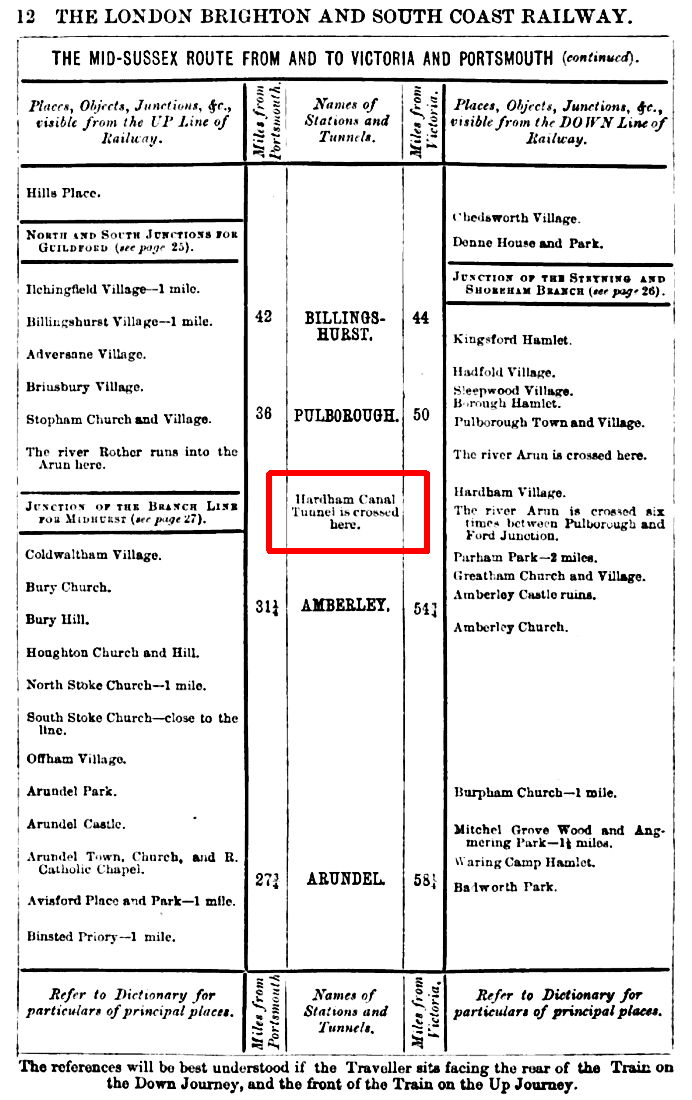

Hardham canal tunnel listed in the list of things to be ‘seen’ along the London Brighton and South Coast Railway’s route. This description is from a period when the tunnel was still actively in use, and its from The Iron Roads Dictionary and Travellers Route Charts of the English and Welsh Railways (1881). Google Books.

After closure of the Hardham cut, the railway became somewhat concerned about the tunnel’s condition. Its Mid Sussex line (opened in 1863 from Horsham to Arundel Junction) passes barely 13ft over the crown of the tunnel. The reason for that is the railway was dug by way of a cutting which brought the tracks closer to the tunnel in question. The cutting itself (and the previously mentioned footbridge) can both be seen on Google Streets.

The tunnel had last used been for boating in the 1890s and evidently it was no longer suitable for navigation of any sort. Upon concerns of possible subsidence, the railway decided to strengthen the disused canal tunnel and they did in 1898 by building a shaft through which they infilled the tunnel almost to the top of the arch. This work was also undertaken where the former Midhurst line too crossed the tunnel.

In terms of what could be described as ‘problematic’ canal tunnels (Hardham was infilled as a precaution – not that it presented any actual problems), another example comes to mind and that’s the one at Southampton where the Salisbury and Southampton canal’s own tunnel, completed but never used, had given problems for the later railway tunnel built through the same ground.

The Southampton tunnel, by way of being on about the same level, was partly demolished for the railway. It did continue to be problematic however. After substantial backfilling was undertaken, the railway tunnel’s integrity became far more secure – and there’s almost no way the former canal tunnel can pose any sort of threat.

Hardham is a different case however because it forms an air space beneath the railway and even though it hasn’t shifted in any sense, its why there’s this interest in the tunnel’s condition. If any issues arose with the tracks in the immediate vicinity the engineers would want to know if it was the canal tunnel that was giving problems. In the 1940s the Southern Railway decided to facilitate an easy means of carrying out inspections of the tunnel below their tracks.

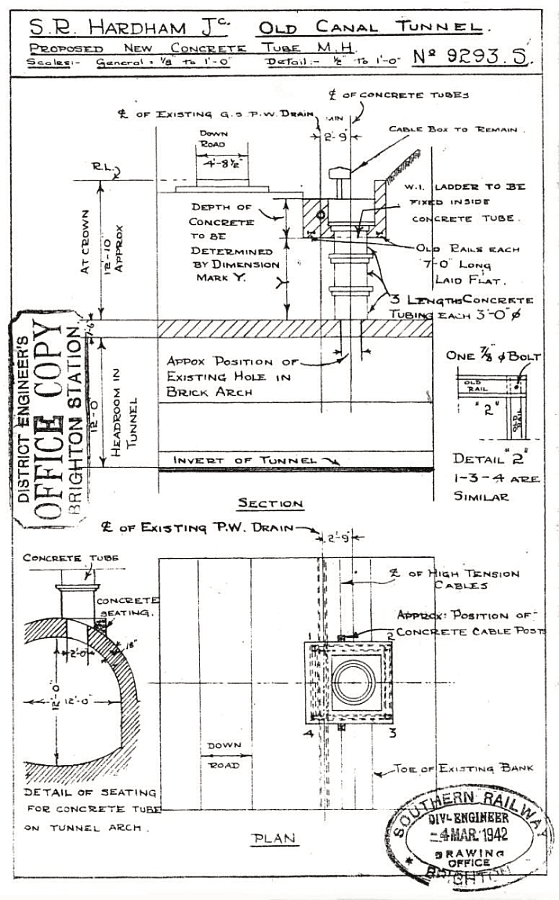

Southern Railway plans for an access shaft, 1942. Internet Archive.

In the early part of WWII the Southern Railway drew up plans to build an easily used access point down into the tunnel for the purposes of inspection, as the above drawing shows. The shaft and its ladder still exist to this day as the pictures below show.

The infilled section of canal tunnel with the ladder & shaft installed by the Southern Railway. 28 Days Later.

The access shaft built by the Southern Railway in the 1940s. Its clear there’s not a lot of ground between the railway formation and the top of the canal tunnel and that is because the railway was dug in a cutting through the hill. The concrete slabs are no doubt intended to prevent anyone gaining access to the railway itself. 28 Days Later.

Hardham tunnel is Grade II listed. It was given this status in 2019 for a number of reasons including it being ‘an unusual example of a canal tunnel built on a river navigation’.

It must be said the provenance of the tunnel is unclear and attempts to prevent explorers entering the tunnel have not been successful. There have been a number of explorations of the tunnel – some of which can be seen on Youtube as well as 28 Days Later. These risky trips are unfortunately the only way this historic structure can be somehow fully appreciated. One such trip was made in 1953 and that can be seen here at A forgotten Canal Tunnel Explored. In the comments section one of the Southern Railway’s engineers relates briefly how the 1898 work to infill the canal tunnel was achieved.