This is a special post for the 160th Anniversary of the Hammersmith & City line! Everyone knows the history of Metropolitan Railway as the world’s first underground line on 10th January 1863 between Bishops Road and Farringdon – but that was not even how the line was going to be built. Long before they had even started building the line to Farringdon extensions to the system were under consideration with some already approved by Act of Parliament. The Hammersmith & City opened to fanfare on 13th June 1864 – one hundred and sixty years ago, and through trains ran began running from Farringdon to Hammersmith. Yet this should have been opened at the same time as as the Farringdon line. The later opening was however due to a disaster.

This is an extended version of my post which was first published in London Reconnections.

The entire length of the railway alongside Bartle Road in Notting Hill, London W11, was the scene of a major disaster that befell the capital’s sibling underground network.

A calamity that was so large….

That calamity was so large and yet so under reported perhaps because it was overshadowed by the new line to Farringdon. The world’s eyes decsended upon Farringdon line because it was a total novelty – and when things went very wrong as they did (see this post on the Metropolitan Railway), the media dutifully reported it. There’s also photographs plus numerous drawings and sketches of the Metropolitan’s construction thus historians have had a field day in terms of the world’s first underground railway

The section to Hammersmith has received scarce attention even in modern history (Londonist gave a brief mention of the viaduct however). Essentially what happened was much of the line was to be on a viaduct from a point west of Notting Hill station (Ladbroke Grove) to a point north of Hammersmith. And what happened is the first section of that viaduct collapsed entirely!

It was no doubt the first ever major accident to hit London’s underground railway system. And no-one’s ever mentioned it took the best part of two years for the Hammersmith & City’s construction to get back on track.

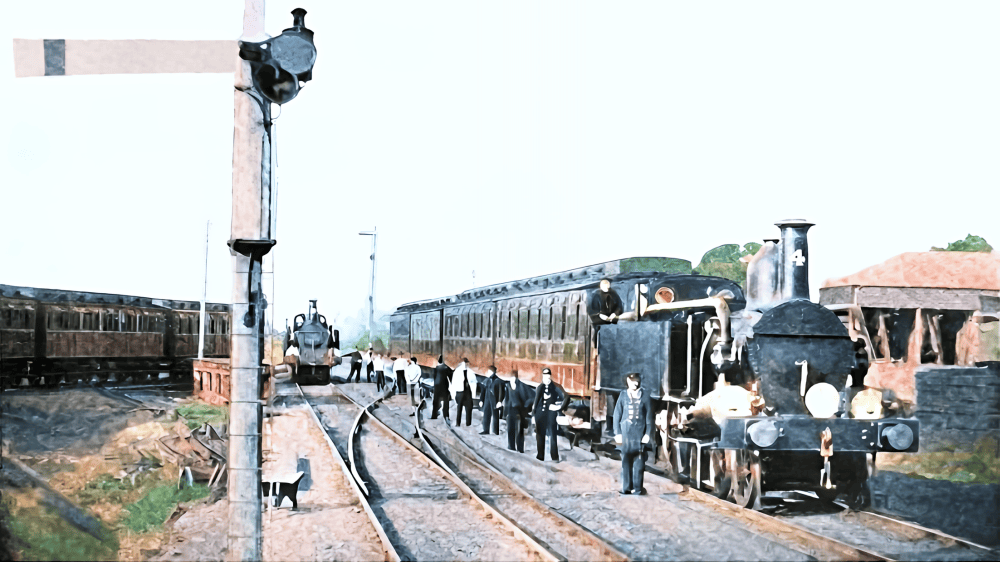

Broad and narrow (standard) gauge track at Hammersmith in the mid 1860s. Only the ‘narrow gauge’ was operating by the time this picture was taken. Hammersmith station had not yet been built thus trains stopped at a temporary station (where a train is seen out of view to the left) at what would later be Grove Road station on the Kensington and Richmond line. Colourised crop of a picture featured in Locomotive, Railway Carriage and Wagon Review 1923.

Historical background to the Hammersmith and City Railway…

The mixed gauge Hammersmith & City Railway opened from a junction with the GWR, at what is now Westbourne Park station, to Hammersmith on 13 June 1864. Built by the GWR and Metropolitan Railway it was set up as a separate company even though the property holder remained fully the GWR. The Hammersmith & City Railway was worked by the GWR on the broad gauge until April 1865 when the Metropolitan Railway took over working, and the GWR broad gauge trains just worked to and from Kensington, Addison Road until 1869 when the broad gauge rails were lifted. The line had become the joint property of the Great Western and Metropolitan companies on 1 July 1867. (A History of the Great Western Railway by Colin C. Maggs 2013).

Hammersmith, Paddington and City Junction Railway as the line was first known. Building News and Engineering Journal 1860.

The line was originally to be known as the Hammersmith, Paddington and City Junction Railway The bill was passed on 22nd July 1861 and there was every intention it would be built concurrently with the line to Farringdon. The new line soon became known as the Hammersmith and City Railway and later bills were made under that title.

Through traffic was always an intent of the new railway and from the very beginning there were trains from both Farringdon and Moorgate Street to Hammersmith and Windsor. Indeed the platforms at the original 1863 Farringdon station included one known as the Windsor platform! The fact the GWR and the Metropolitan jointly ran the line saw to it that Paddington, uniquely amongst all the major London rail termini, happens to be the only one with a London Underground line running through it.

The Hammersmith line was run by a joint committee which consisted of both GWR and Metropolitan representatives. It also had separate headquarters to that of the Metropolitan and the joint committee was based at Paddington for a good part of its existence before accommodating new premises right next door to the Metropolitan Railway’s head offices in Craven Hill!

At one time the Hammersmith and City Joint Committee and the Metropolitan Railway Company had their headquarters adjacent to each other but remained separate entities! It was perhaps this that prompted the Metropolitan to build Selbie House at the rear of Baker Street station to expand its own interests as well as accommodating the other party. The above pictured premises is of the former H&C Joint Committee and Metropolitan Railway Company on Craven Road, London. The premises now form, among other things, a hotel.

Interestingly the line remained in the ownership of the GWR as the property holders, and this ensued throughout the Big Four and nationalisation. Nevertheless through traffic remained on the Hammersmith and City line right into the modern British Rail era with Class 117 DMUs from the Metropolitan line at Paddington to Reading, Windsor, Staines and Uxbridge – and it was not until 1971 when BR (Western Region) had completely relinquished its ownership and management of the line.

Example showing a Class 117 on a Windsor & Eton Central service at Paddington. These DMUs would be equipped for use on the electrified LT lines – a legacy of the GWR having had joint operations with the Metropolitan Railway since 1863. The journey entailed would utilise the Hammersmith & City line as far as Subway Junction before reaching British Railway tracks proper. Image created by the author in 2020 for a different post.

For most if its life there was a separate company and since the line wasn’t even ‘underground’ there’s no doubt a number of reasons why the Hammersmith and City has remained in relative obscurity in relation to the main London underground network. Unsurprisingly there’s little subject material on the Hammersmith & City viaduct disaster and any photographs of the Hammersmith & City line in its earliest days are almost non-existent.

The original bridge at Notting Hill (Ladbroke Grove) was replaced by the UK’s very first all welded steel structure in 1938. The locality’s other overbridge is at Portobello Road and are the only examples built within the line’s short embanked section of about 280m. The remainder of the line’s almost entirely viaduct with some brick or steel overbridges. Pic colourised by author. The Library Time Machine has some very interesting archival pictures of the new 1938 bridge installation.

Construction of the Hammersmith and City at first progressed well from Green Lane junction (Westbourne Park) to Notting Hill station – and it did look as if the route would be completed well ahead of expectations.

The line was to be furnished with nearly two miles of railway viaduct, and this was in fact the first ever lengthy viaduct to be built on what is now the London Underground system. Long viaduct sections are no doubt a feature of several of the capital’s railways and the London and Greenwich Railway was the first such example to be built.

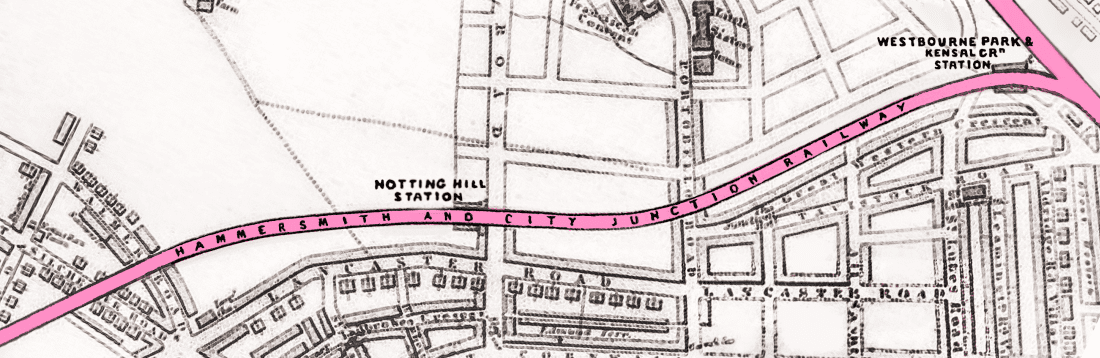

In this map specially created for this post based upon others of the time, practically the entire H&C route from Green Lane junction that was built by November 1861 is shown. Its interesting the cartographers of the time used a pink colour which closely resembles the H&C’s present pink/salmon line colour!

By the winter of 1861 the route had been built from Green Lane to the site of Latimer Road station whilst the new connection from Kensington Junction (aka Latimer Road Junction) to the West London Railway was also under construction. However disaster struck this rapid progress…

An entire viaduct on the Hammersmith & City line collapses…

On the night of November 6th 1861 practically the entire viaduct to Latimer Road collapsed. Six construction workers were killed. What happened is still open to debate, but one thing is known, the ground wasn’t very stable. A long spell of very wet weather exacerbated the problem. This was all but completely unknown to the line’s overseers who had deemed the lengthy viaduct section complete and could even be used by construction trains.

The Hammersmith line viaduct collapse detailed in The Dublin Builder 1862.

The engineers of the line were Messers Fowler and Wilson and this was in fact Sir John Fowler’s company. Fowler was of course the engineer responsible for designing the world famous Forth rail bridge. John Fowler (as he was at the time) was engineer for both the Metropolitan Railway and its extension to Hammersmith. The building contractors for the line were Rummins – however the viaduct was actually built by sub contractors John Holden. William Wilson was the resident engineer and the one who directed the viaduct be shored up urgently.

Arches 12 to 14 (right to left) are seen here. Which of the original arches had been the culprit?

As has been mentioned, at the time it was thought the viaduct was finished and ready for use. But no sooner than the timbers supporting the viaduct and its arches were removed on or about 1st November 1861, something began to go very wrong. All was fine for about a week until the morning of 6th November 1861 when a crack appeared in one of the arches (either number 12, 13 or 14 about where the old ditch was). The arch in question soon took on a quite distorted appearance and alarm bells were set ringing among the site’s workers and supervisors.

The London Underground system consists of a considerable amount of lengthy viaduct in some cases stretching a number of miles. Whether it was the Hammersmith & City in the 1860s or the Piccadilly Line in the early 1930s the technique for construction remained basically the same (as would be for arched brick doorways, windows or any other arch design) which is to use timbers to form the structure that is desired. Once the timbers are removed it is at that point a viaduct is considered to have been completed. My London.

The line’s resident engineer William Wilson decided the problem arch plus the three either side should be shored up urgently. By nightfall things had gone from bad to worse and an army of frantic workers began shoring up more of the viaduct from the west side onward. Efforts to quell the distortion was to no avail. First the piers supporting the problematic arch collapsed followed by four arches on the Hammersmith side. Three on the City side subsequently went down and so on until fourteen arches in all had fallen.

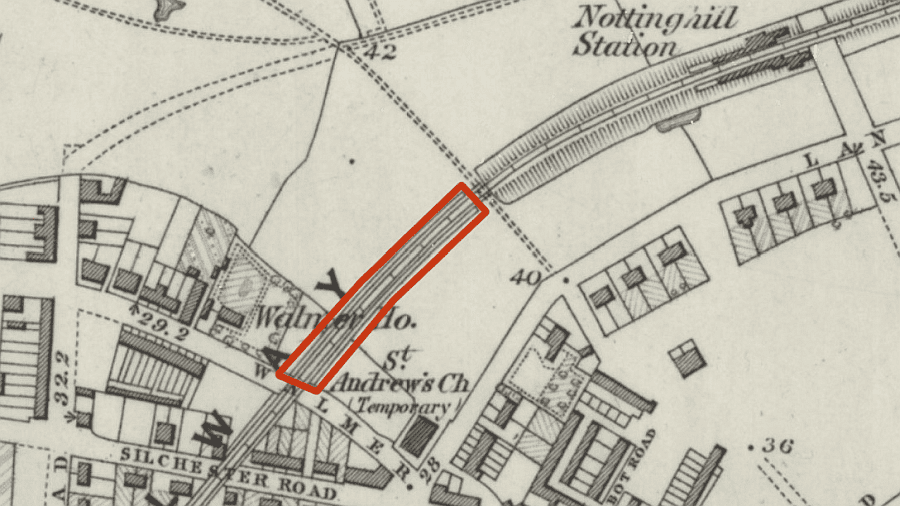

Location of the viaduct on the Hammersmith and City Railway probably mid 1860s. Note the lack of buildings around the site at the time which was perhaps quite fortuitous. Notting Hill ( the present Ladbroke Grove) station can be seen at the top. National Library of Scotland.

As has been reported six workmen were killed. It is said the men were found under where the third arch to the west of the faulty one had collapsed. It has been said one of the workmen’s wives and his daughter arrived with his supper just at that moment and it was claimed they too were buried by the viaduct’s collapse. Since the inquiry does not mention extra fatalities it can be assumed the wife and daughter were later found quite safe.

The Hammersmith line viaduct collapse detailed in The Annual Register, Or a View of the History and Politics of the Year 1862.

The lives of the workers who died ranged from 19 years upwards and the last of the bodies was not recovered until several days later. It must certainly have taken the railway’s contractors several months to clear the collapsed viaduct from the area then ensure the ground was drained properly and fully solid before a second new viaduct could commence construction. No doubt the inquiry which followed took precedence and construction work on the railway was largely slowed down until the court’s investigations were concluded and a decision made on how the disaster unfurled.