S7 stock on the offending section of viaduct. On the right can be see the signal sited just west of Bartle Road, and on the left can be seen the signal by St Marks Road.

In the above picture two sets of colour light signals can be seen but these signals are no longer in use because the line now runs on CBTC. However these mark the beginning and the end of the viaduct section which collapsed in 1961. The entire viaduct is on a gentle curve that turns the railway from an initial western alignment to a south western direction. Part of the parapet belonging to St Marks Road bridge can be seen – that’s roughly 425m (or 1395 feet) from Latimer Road where this picture was taken!

How long is fourteen arches exactly? Each section of the line’s viaducts are built in the same style and the section by the Westfield Centre has fourteen arches visible which indicates the total length of viaduct that collapsed in 1861. Fourteen arches equates the full eight cars of a S8 stock train however the H&C and Circle lines’ S7 stock equates twelve arches. It must be remembered there were nineteen arches in total and fourteen of those collapsed.

London Reconnections responses & other observations

I didn’t know where to put this section because it contains some other information about the Hammersmith viaduct collapse. But here will do! As some will know, this article was originally published in a shorter form in London Reconnections on 13th June 2024. One of the interesting finds from that was the fact the noted London Underground historian Mike Horne had written about the disaster as the following comments reveal:

- Antony Badsey-Ellis says:

The viaduct collapse is mentioned in Mike Horne’s history of the H&CR, although in less detail than this article which pulls together a lot of useful information. - Pedantic of Purley says:

It was once suggested to me that the more important the line the less well documented it is and vice versa.The Waterloo & City has an lengthy and detailed book devoted to it, The Aldwych branch has an excellent book on it (written by Antony Badsey-Ellis – the commenter above! – and Mike Horne). It is easier to find out about the Brill branch than it is the Hammersmith & City railway. The only real excuse is that the history is ridiculously complicated for such a small line. It is not helped by originally being a joint line with the GWR meaning that GWR books almost ignore it and books about the Metropolitan Railway also seem to largely give it a miss. Mike Horne’s book on the subject (probably the best there is) is out of print and not easily obtainable at a reasonable price.So it is great to have an article on one aspect of it that has largely been ignored. Better still the article is well-documented with reference to sources.

I was intrigued that Mike Horne had indeed referenced the viaduct disaster, however despite knowing of his work written in 2014 on the Hammersmith & City, I had never seen a copy of the book itself, thus evidently I was most unaware of the contents of that work. Luckily I managed to find a copy at reasonable price (£5) at the Routemaster 70th Anniversary event in Chiswick Park on 21st July 2024.

This means I have now seen sight of the actual book and it is very interesting indeed. As for the H&C viaduct disaster itself, there is a paragraph or so on the matter. While its not a lot it is without a doubt the most detailed reference that could be found on the matter prior to the publication of my article in London Reconnections. Not only that it mentions the entire viaduct collapse took place within a minute. I have scanned the contents of that and it is reproduced below if anyone wishes to refer to that.

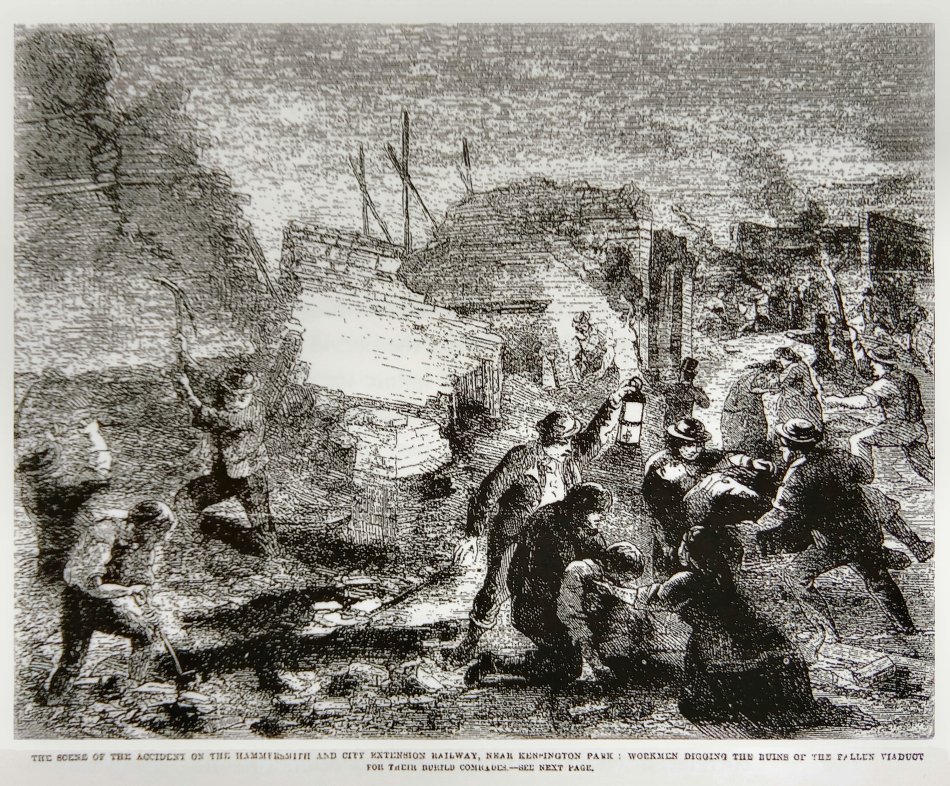

There is also a drawing in Mike Horne’s book from the Illustrated London News on the disaster. The actual date of publication is not known as that is not given in the book – however it must be about the third week in November of 1861. So far this seems to be the only known picture of the fallen viaduct. The line between Paddington and Farringdon is well documented from about April 1862 onward, but there’s no doubt 1861 was perhaps a tad too early for any photographer to have captured anything of the actual viaduct collapse.

The scene of the accident on the Hammersmith and City Junction Railway near Kensington Park. Illustrated London News via Mike Horne’s book The Hammersmith & City Railway 150 Years.

The location alluded to in some reports is as being near Kensington Park, and yes that is very likely correct. Its within the present Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and the reason this is brought up is because in Mike Horne’s book the picture of the destroyed viaduct is described as being in that location and there’s presently a road by that name which reaches almost to where the railway runs into Ladbroke Grove station. However the viaduct in question is actually further west and it seems the immediate vicinity didn’t have a proper name until Latimer Road came along a few years later.

If there had been anyone at the time with any intent of documenting the new railway, their focus would, as has been pointed out earlier, been focused on the section from Paddington to Farringdon. Even so, anything earlier would have been very limited as is evidenced by two photographs taken of the Victoria Street (Farringdon) terminus (one of those can be seen here). These were taken possibly because the photographer was perhaps more interested in the clearance of the area’s disreputable slums. The locality previous to the construction of the new railway had been one where thievery, violence and murder were rife.

Outcome of the viaduct disaster

One outcome was a delay in the line’s construction. Previously good progress had been made on Section One of the contract as far as the site of Latimer Road. Work did not fully recommence until November 1862 and by April 1863, 69 arches had been completed to a point just west of Kensington Junction where Section two of the contract commences. By August 1863 construction had seen the viaduct completed as far as arch number 92 at Wood Lane.

Strangely no mention seems to have been made ever again of any calamity to befall the line’s construction, however a majorly dispute with a married couple who resided in the Wood Lane area arose in regards to the viaduct’s construction – that made it into the news and was even challenged in the courts!

Its as if the viaduct disaster had never happened!

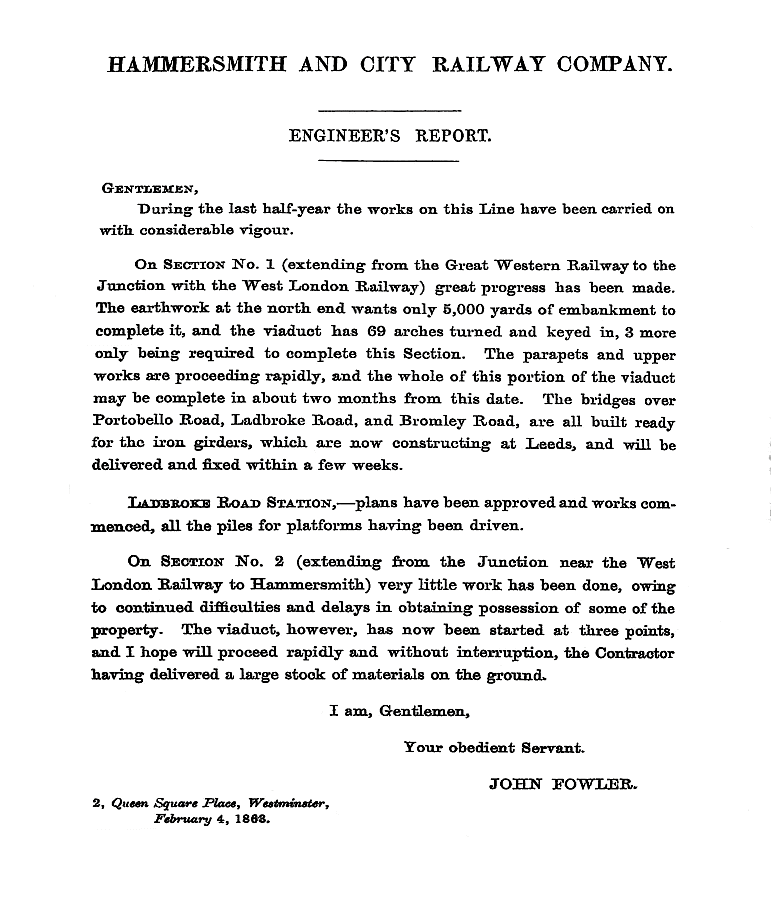

John Fowler’s report to the Hammersmith & City Railway February 1863, detailing the ‘considerable vigour’ with which the line’s viaducts construction was progressed. This is a hugely cleaned up image of one found on the Internet Archive.

There’s one thing from the above report – even though its not discussed at all here, and that the amount of delay the line had incurred as a result of its viaduct collapse. There is no doubt part of the collapsed viaduct had to be left intact for the ensuing enquiry which took more than a year. Also the time in lieu for the directors and contractors and workers to attend the inquiry and John Fowler himself had to attend it too. He gave a fair amount of evidence detailing that the viaduct had been built well and at no time was construction was suspected to be below standard.

To reiterate, somewhere in the vicinity of the length of 175 meters (575 feet) of brand new railway viaduct had collapsed. Of nineteen arches of the viaduct along the full length of the present Bartle Road in London W11, fourteen of those had collapsed entirely. Its quite fortuitous that the viaduct, the second such structure to be built along this section, was previously quite hidden but can be easily seen today – and one can walk alongside and imagine the scale of the disaster that befell the first viaduct built.

In this late 1960s view located at the corner of Bartle Road and Kingsdown Close the Hammersmith & City’s viaduct is quite obscured by industrial buildings. The Library Time Machine.

Pic I took in May 2024 to compare with the one taken in the late 1960s. All the area’s former industrial buildings have gone and the viaduct is more visible. Its full length can be walked from here to St. Marks Road.

In this early 1960s view the viaduct in question can be seen quite hemmed in by industrial buildings and town houses. The large church still exists. A transport depot can be seen next to the railway. The site of this is now Bartle Road. To the rear of the depot (and out of sight) was the notorious Rillington Place where the mass murderer John Christie lived. The Library Time Machine.

The inquiry and subsequent fallout

When construction commenced in August 1861 on that very section it had been a dry summer and it was therefore not possible to ascertain the ground was essentially unsuited for the purpose it was being put to. The course of the old ditch wasn’t actually built upon as the piers stood either side of this. As the year drew on and the autumn arrived things began to change and the ground became very waterlogged. No-one noticed however because the entre viaduct was kept rigid by the use of construction timbers which were of course essential in order to enable this (or any other viaduct) to retain its shape and form. Once the work had been deemed completed these timbers were removed and contractors’ trains were even allowed to pass upon the viaduct. It was alleged at the inquiry the use of these trains had caused the viaduct to weaken.

Bombs hit this H&C arch at Wood Lane during 1940. The viaduct stood up well in spite of this and there’s no doubt these were very solid structures. LT Museum.

One would perhaps wonder why there’s little on the matter especially given the scale of the collapse. Evidently the world was focused upon the Metropolitan Railway’s Farringdon line so the Hammersmith disaster sort of passed by. It wasn’t just that. The courts found no laws had been broken thus no blame was ascribed for the calamity and the severity of the incident was mitigated somewhat. The deaths of the workers were deemed to have arisen from accidental causes. There was outrage over that of course but since no culpability could be attributed, the fallout was dampened.

As John Fowler’s report (shown above) from February 1863 demonstrates, there was no doubt an embargo of sorts on the disaster. It wasn’t exactly something the sibling underground railway would wish to revisit especially when there was a considerable amount of suspicion as to the materials used and the ability in question of the engineers, surveyors and workmen who had planned and built the structure.

Once an open verdict had been given by the courts, there was no doubt a considerable amount of opinion and criticism upon the disaster – and it was this the Hammersmith & City company wanted to deflect – for in the minds of others it was deemed the lines’ engineers, contractors and the companies supplying materials had all been complicit in one way or another.

The Building News in fact published a list of things suspected of being responsible for the viaduct’s collapse in its publication on November 28th 1862. It explained what they thought had gone wrong with the viaduct’s construction. They had believed that with the correct materials and mixtures the viaduct should have had no reason to collapse. ‘It is not right that human life should be endangered and sacrificed through buildings of this character being reared in a weak material…’ As the Building News cited, their concerns was because it had been noted other railways were too employing a false economy of using inferior or suspect materials.

The noted engineer Joseph Cubitt was brought in to inspect the damage and report upon what could have gone wrong. Cubitt’s verdict as given to the inquiry was the softening of the clay and or soil. The quality of the materials was perfectly satisfactory. Cubitt referred to a similar accident at one of his own sites although it is now known where that was.

The jury themselves had admitted they suspected the concrete used in the foundations near the said ditch was ‘not of a sound and proper kind.’ John Fowler basically proved the jury wrong. Besides the concrete, the quality of the mortar and lime was also blamed as were the bricks used in construction. Companies were also suspected of having involvement of some sort in the matter like supplying inferior materials. One such company, Greaves and Kershaw of Paddington, went so far as to put out a statement citing that none of their lime had been used in the viaduct’s construction.

Greaves and Kershaw’s statement November 1862. Google Books.

The disaster was ultimately ascribed to what was largely a series of unknown factors thus it seems blame couldn’t really be attributed no matter how hard the inquiry sought evidence of any negligence in the viaduct’s construction. John Fowler for example refuted the jury’s suspicion of inferior concrete being used by demonstrating the concrete samples brought over from the accident site and which the jury were looking at had in fact been disintegrated by the lateral movement of the piers.

Every engineer and every contractor that was examined were found to not be at fault and where less than ideal materials had been suspected of being used in the viaduct’s construction, samples were brought to the inquiry and analysed and shown to be essentially without fault. Thus there was no option really other than to conclude there simply wasn’t anyone who could be blamed for the calamity.

The matter no doubt faded into obscurity and has been almost totally overlooked by historians of both railways and the Underground.

A shorter version of this article was originally posted on London Reconnections – the arrangement (as agreed with LR) is any posts for London Reconnections will be published in shorter form.