The reason for the canal tunnel construction – RAILWAYS!

Rove is special since it’s a canal tunnel that was constructed mostly with railway assistance. It was a huge and intricate network of railways that were many miles long and used at least two different gauges, not just a little contractor’s line, as shown in a few examples in the previous parts of this series. Passenger trains were also in operation; these were for the workers, and while the majority of them travelled through the tunnel, it appears that these were also used on other routes connected to the canal’s development.

It is often overlooked why this tunnel was constructed. Because of the railways, it was a matter of need! The port of Marseilles was surrounded by terrain that hindered its development, and the only significant export route was by railway, as was discussed in the French parliament in 1895. The city was, to put it mildly, at the mercy of the railway corporations, who had the power to determine the tolls for the subsequent transportation of products.

As the world goes, most successful ports were no doubt to be found by the sea – but these also had a river that headed inland (with canals linking up to that too) which no doubt ensured a port’s prosperity. Thus most ports were the agent of their own fortunes and not that of some railway company. What was possibly worse was the railway company – the Paris, Lyon and Mediterranean (PLM) was remotely headquartered in the French capital – and not the Mediterranean.

A junction of waters was no doubt an important node in ensuring the success of any of the major seaports that are to be found around the world. Marseille wasn’t one of those. There wasn’t a river that could make the municipality’s fortunes grow. To make things more difficult, the city being the capital of the Côte d’Azur region, was surrounded by difficult terrain (these are the Estaque mountains whose highest point is Pilon du Roi at 710metres or 2329 feet). Its nearest commercial river, the Rhône, could only be reached by way of a difficult passage via the Mediterranean sea.

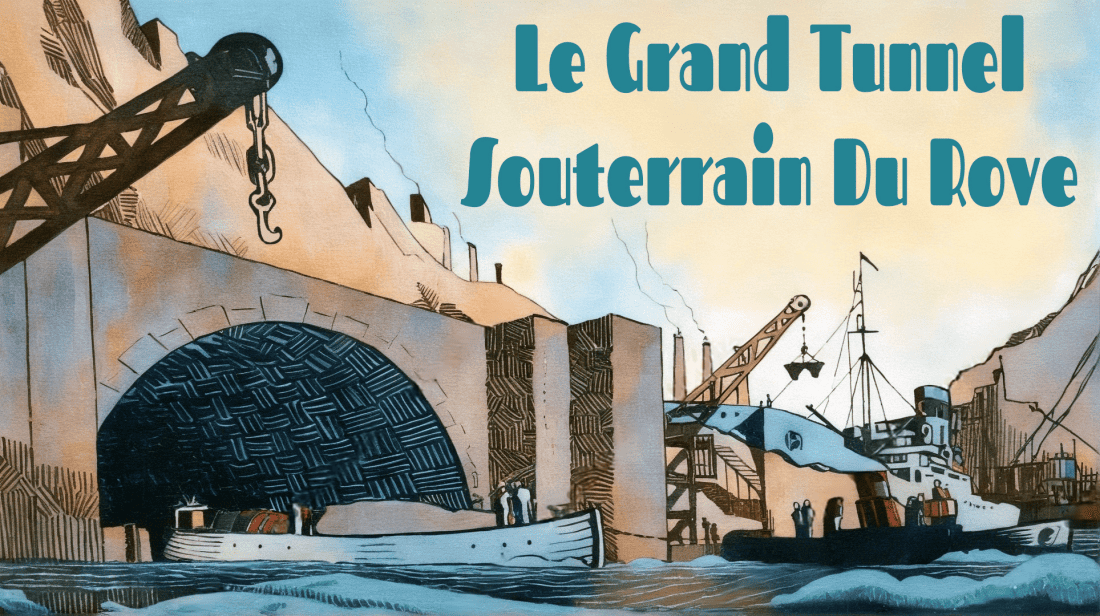

The Rove tunnel as it is these days. It has lain unused for sixty two years. View into the tunnel from the northern portal. Wikipedia.

The Marseille-Rhône scheme including its tunnel is approved

It had long been acknowledged that the railways’ monopoly needed to be addressed. Marseille required an artificial river that would bypass the lengthy diversion to the Rhône and connect to every region of France and beyond. Since the 1840s, the city had been concerned about this. Schemes were occasionally proposed, but none of them ever materialised.

In the 1890s, the plan was ultimately adopted. The prominence of the hills that encircled Marseilles was the reason for the canal’s incredibly long tunnel, and the tunnel’s sheer size was a result of the need to handle any ships that could use the Rhône. Therefore, a width of 17 meters at water level was considered required for vessels that were 14 meters wide. The tunnel’s water channel would be three meters deep.

The Minister of Public Works, after reaching an agreement with the Minister of Finance, invited the Marseille Chamber of Commerce to replace the financial arrangement originally conceived for the construction of the Marseille-Rhône Canal with a new arrangement similar to the one the Senate had just adopted. By a resolution of January 22, 1895, the Chamber of Commerce, considering that the planned canal ‘is a work of salvation whose implementation is essential, and that this implementation must be ensured at the cost of the greatest sacrifices, for it is the only, but it will be the very effective, remedy for the current situation in Marseille…’

In terms of the new Marseille – Rhône waterway, it would be a considerable undertaking…

The canal would be 54 kilometers long. It would run from the Madrague Basin at the northern end of the port of Marseille to the Rhône at Brasmort, about ten kilometers upstream from Saint-Louis.

Leaving Marseille, this canal would follow the coast past Cape Janet and L’Estaque to Pointe de la Lave. It would cross the Rove mountain range through a tunnel approximately 7,500 meters long and would open at Marignane in the Bolmon Pond. It would run along the southern shore of the Berre Pond, pass near Cape Trois-Frères, where the small port of La Mède would be created, and arrive at Martigues, which it would cross. It would then follow the maritime canal between Martigues and Port-de-Bouc, then part of the Arles-Bouc Canal between Port-de-Bouc and Pont-à-Clapets. From Pont-à-Clapets, the canal would follow the shortest route to the Rhône, where it would end at the Bras-Mort lock.

The canal would be 2 meters deep between the Rhône and Port-de-Bouc and 3 meters between Port-de-Bouc and Marseille. The width of the basin… would be at least 50 meters in the Gulf of Marseille and the Berre and Caronte ponds; it would be 46 meters between Port-de-Bouc and the Rhône; finally, it would narrow to 17 meters in the Rove tunnel and the small trenches of La Mède. The Rove tunnel would be 22 meters in total height. 50 m wide at the towpath benches and 16 m high above water. (quotes from Google Books – Annales de la Chambre des Députés 1895).

The promotion of the canal would lead to a huge reduction in costs. Transport by railway cost 30 francs per ton. With the new waterway this would drop to about 15 francs per ton. Not only that through traffic would be enabled for vast quantities of goods between Marseilles and Paris – something that wasn’t easily achievable by water at the time. A map of the time showed all the advantages the new waterway would bring including direct water connections to most of France and parts of Germany and Belgium.

The canal would be substantially funded by the State and cost 80 million francs. The local authorities would provide an initial fixed subsidy of 40 million, and these were the Department of Bouches-du-Rhône with 6,666,666 francs; The City of Marseille with 6,666,666 francs; The Chamber of Commerce with 26,666,668 francs.

Legislation for the construction of the Marseille-Rhône canal was approved by the French state in 1900.

Leave a Reply