The Scole Railway is one of Britain’s most obscure lines. It was a system built to serve farmland and market gardens. Passengers were never carried. The Scole Railway is considered one of the pioneer systems built for the specific purpose of serving farms and agriculture. The system connected with the main Great Eastern line at Diss.

The Great Eastern from London and Ipswich to Norwich was once replete with numerous branches and stations yet barely any exist these days on the sections beyond suburbia. Stations from Ipswich were once to be found at Bamford, Claydon, Needham, Haugley, Finningham, Mellis, Burston, Tivetshall, Forncett, Flordon and Swainsthorpe. In the 47 miles of railway between Ipswich and Norwich just three stations remain. Needham Market as it is now known, was fortunately re-opened in 1971. Stowmarket and Diss which serve larger towns have seen continuous service. The others have all disappeared and barely any trace remains of them – and even the branches some of these once served have long gone. Just the Mid Suffolk Light Railway remains in part and that after its tracks had been ripped up for decades. There was one other branch which wasn’t actually for passengers, but nevertheless it was a pioneering line. Alas it succumbed quite early in the UK’s railway history thus very few even know of this line.

During 1973 I was discussing trips I had undertook on my motorbike around the countryside (East Anglia to be exact) with Tim, a colleague, in the architect’s department I worked at. He was an architect and a knowledgeable railway expert – whereas I was a mere junior draughtsman. In terms of the area, one may have seen my rare Southwold railway picture which I took during school holidays. I also completed a stint at the Model Village in Great Yarmouth by way of some good fortune from Mr. William Dobbins. In terms of East Anglia’s railways there’s Alan Bloom’s Bressingham Gardens just a few miles west of Diss, with its numerous railway systems and other steam operated paraphernalia.

There were numerous derelict lines and stations across the region too – some of which were explored. During the 1960s/70s abandoned wagons could be found at Brockford on the former Mid Suffolk Light Railway. However my rail knowledge of the region was no doubt incomplete as when I mentioned Diss and Scole, Tim then asked if I knew a railway had existed between the two places. I did not know, thus I set about trying to find out more about this completely obscure railway.

The Scole Railway is still little known and any history of it is quite rudimentary. In late 2024 I decided the most comprehensive feature ever on the Scole railway ought to be written since 1964 had been a prodigious year for Britain’s Poet Laureate – who happened to be a railway enthusiast too. After some difficult research this post on the Scole/Frenze Farm railway is the result. In any event, this ‘anniversary’ of sorts starts with John Betjeman some sixty years earlier in 1964 when Betjeman visits the Jolly Porter Inn at Diss…

Prologue – John Betjeman visits Diss

Betjeman gazes over the fields towards Diss. Panorama created & colourised by the author from screencaps of the video ‘Something about Diss’ (1964.)

Just a decade or so before I was first introduced to the Scole Railway, England’s famous poet laureate and railway enthusiast had visited Diss and it became one of his favourite towns. He arrives at the station on a train from Liverpool Street. The train is hauled by a Class 37 and upon arrival the station master goes to the carriage door and opens it personally for Betjeman to step off the train and onto the platform. Betjeman immediately places his hand luggage on the platform and stands to gaze out across the fields into the distance where the town was actually situated.

Its 1964 – and Poet lauterate/railway enthusiast Sir John Betjeman discovers Diss! Actually the town was somewhat under a mile west of the station – all that could be seen between here and the town were fields which Betjeman is looking upon. Nevertheless Diss has grown so much the station is now pretty well within the town’s boundaries! Its said Diss became one of Betjeman’s favourite towns. Alas he probably did not visit Scole and saw the splendid hotel nor even knew about its railway! Youtube.

The Jolly Porter Inn is right opposite the main entrance to the main line station – in fact the Inn was within the station’s operational environs – quite an unusual situation for a public house. It was sited amdist the various tracks that formed the station’s moderately substantial goods yard – railway tracks ran either side of the building. This unusual situation once featured in a court case (discussed later) involving the Scole Railway against the might of the Great Eastern Railway!

Betjeman enters the passage that led to the Jolly Porter’s main entrance. Rails (and a foot crossing) are quite evident at the bottom of the picture – the tracks led to the coal yard – it was all part of the station’s goods yard and indicative of a unique layout that once existed. The Scole railway ran past the building just visible at the end of the passage. Youtube.

To compare, here’s a picture on Flickr which shows the same foot crossing in 1976 looking towards the station buildings – the Jolly Porter by then no longer in existence. The inn’s lease expired in 1973 – and it was demolished soon after.

There are very few pictures of the Jolly Porter Inn – and also surprisingly of Diss station too! Interestingly the long gone stations on either side of Diss station – Mellis, Tivetshall, Flordon and Forncett – fare much better in terms of historic photographic coverage! Thus Betjeman’s film is quite unique because it captures a train arriving from London at the peak of the Eastern Region’s full on dieselisation programme – there were barely any steam locomotives left in the area by this time. Not only that the film essentially captures the unusual arrangement the station goods yard had. Thus its only Betjeman’s film which appears to be the only evidence that shows the Jolly Porter in its older historical context.

Betjeman, later one of Britain’s most loved Poet Laureates, is seen here at the main Jolly Porter entrance. Betts siding, a remnant of the former railway alignment, could once be seen passing the end of the building just out of sight to the right. By the time of Betjeman’s visit the siding had vanished. Youtube.

The Jolly Porter was once the centre piece of the Scole Railway – at least in terms of the line at Diss. The railway’s workers loaded and unloaded the line’s wagons and some of the produce was stored in the adjacent barns in readiness for the onward journey to London. Not only that, the line’s wagons were marshalled onto the Great Eastern’s goods trains in order to be conveyed through to London Bishopsgate goods station, and thence transferred to horse and cart for delivery to the city markets – including Leadenhall and Covent Garden. The Inn was a place where workers could take advantage of a break and socialise, and the building was once surrounded by granaries and warehouses owned and constructed by William Betts – more of whom we will read later.

The Eastern Union Railway reaches Diss

The railway came to Diss in 1849 but not before consternation had been raised at its arrival – and that curiously by a person named Betts. It might have been a distant relative however the one in question was Sophia Betts (of the Wortham family lineage). She owned a fair bit of the land that the new railway and its station would require and this was compulsorily purchased it seems.

Sophia Betts held a grudge against the Diss Railway Extension Company which had built the railway to the town as part of the Eastern Union’s new route to Norwich. Sophia Betts launched a tirade against the new railway (as well as against Rowland Hill and his postal reforms) and a satirical ode was made using text cut from newspapers to ‘honour’ the power of the railroad:

The Railroads we find are falling down fast,

The pace was too rapid, of course could not last.

Alas! Our good ancestors little did dream

Their descendants were doomed to be blown up by steam;

Nor thought that the cash they collected with care

Would be stuck in the railroad to purchase a share. (Internet Archive).

Services from Ipswich to Diss began on 1 July 1849 and later in the year the line was completed to the Eastern Union’s new terminus at Norwich Victoria station. It would be a number of years before the city’s other station, Norwich Thorpe, became the main terminus for rail services from London.

The Frenze estate builds its railway from Scole to Diss

It took another Bett before things changed. It was a William Betts who had recently become owner of the nearby Manor of Frenze which oversaw a vast tract of estate to the east of Diss (conversely its church covered one of the smallest parishes in the country). Instead of Betts being at odds with the new Eastern Counties Railway he decided to use that to his advantage in conjunction with the vast new market gardening venture being set up across the Frenze estate. Betts set about building his own railway in order to take advantage of quick conveyance of his agricultural produce to London, which meant food could be on the city’s markets freshly delivered the day after being picked. A number of wagons, all of which were designed by Betts, were employed as a means direct transit from the Scole railway to London’s Bishopsgate terminus. Some other wagons were also built however these were solely for use on the estate and carried large water tanks.

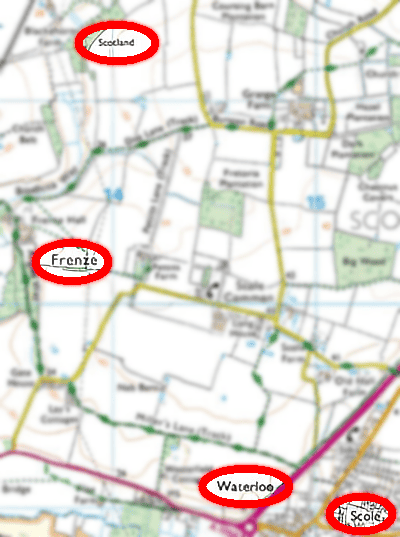

Dr Richard Joby – The Scole Railway – Forgotten Railways No.7 East Anglia David & Charles 1977.

The Scole railway was purely a system built for the purposes of market gardening centred around Frenze Hall near Diss. The railway was fairly short lived and operated for at the most 35 years (depending on which dates are correct in terms of when the line opened). Alternatively known as the Frenze Farm Railway, it connected Betts’ estates to the main railway at Diss thus produce could be shipped to market whilst manure could be delivered throughout the estate.

Wagons belonging to the Scole Railway were in fact taken right through to London where Betts’ produce was unloaded – quite possibly destined for London’s markets such as Leadenhall and Covent Garden. The transfer of produce from rail wagon to horse drawn road wagon likely took place at the Bishopsgate goods yard. In return manure was loaded onto Betts’ wagons and the wagons taken back to Diss. According to the East Anglian transport historian Dr Richard S. Joby, the Scole Railway had been one of the earliest standard gauge market garden lines and was the first of its kind in East Anglia. He adds ‘the line was dismantled in 1886 but is worth remembering as a pioneering enterprise.’ (Regional Railway Handbooks No2 East Anglia p167, David & Charles 1987).

The Scole Railway and its branches. Flickr.

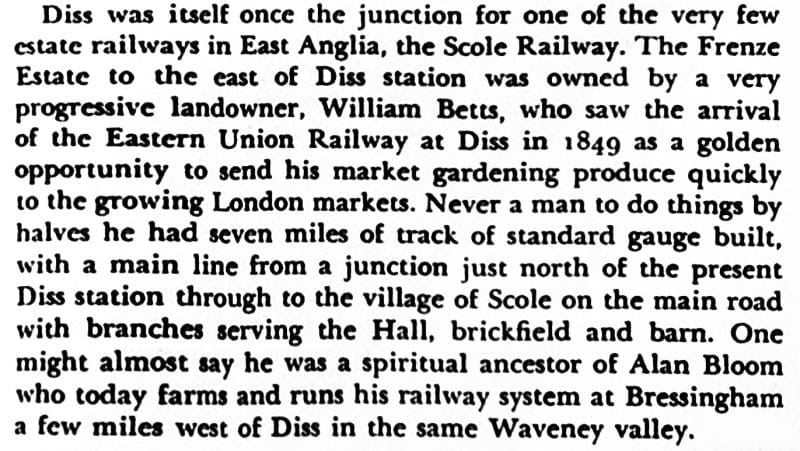

The Scole (or Frenze Farm) Railway headed along two main axis, the first in a general direction eastward from Diss to Scole, and the second in a general northward direction from Waterloo to Scotland. No that is not a joke. The southern end was at some gravel pits near the hamlet of Waterloo and the northern end terminated at Scotland. It is thought this was a corruption of Scott’s Land (as reported in a 1962 article on the line). Curiously Scotland is also marked on modern Ordnance Survey maps!

Some of the places on the railway – including Waterloo and Scotland! Map sourced from Yellow Publications.

The length of the system was seven miles and there were three main branches with other shorter ones coming off those, including one to Frenze Hall itself. The longest branch was to a farm near the road to Burston. Two of the branches (one very short) were of somewhat later construction for these connected to brickyards that William Betts had opened in order to increase the value of his railway and estates. One of those brickyards was just outside Diss station itself where Betts’ railway turned east towards Scole and it seems this was known as the Victoria brick yard.

As for the railway itself, it had two engines, both 0-6-0 locomotives, one named ‘Push’ and the other ‘Pull.’ One of the engine drivers was said to be a William Short. The line had several crossing cottages with staff present to flag the trains across the roads. One keepers was known as Redskin Ramsey, who, after the railway had closed, owned a mill where corn was grounded. He was later found drowned in a large pit that had once formed part of Bett’s brickyard at Diss. In the summer of 1887 he tried to persuade some others from the Jolly Porter Inn to join him for a bathe in the nearby pit, now totally full of water. The other refused so Ramsey went in alone. Before long it was realised Ramsey had disappeared but was nowhere to be seen. His clothes were found in a pile at the edge of the pit. It took two weeks to find his body and this was only possible because the pit had to be drained.

Betts Diss bricks. These may have been delivered to their destination via the Scole railway! Flickr.

It seems Betts was alas unable to use the railway itself because he was disabled (unless a special wagon had been adapted for his use). When the need arose he was taken on inspection tours of the estate by means of a donkey chaise.

The coal yards at Diss station 1920. Part of the buildings that consisted of the Jolly Porters Inn can be seen in the background at left. The line of trees behind the wagons quite possibly mark the Scole railway’s former course. Diss Express.

Here’s a later shot of the same location, looking south. The coal merchant has changed names.

When did the railway actually open?

Since little has been written on the Scole railway, there is some uncertainty about the year the railway had actually opened. Sources suggest 1850, however the Blennerhassett Family page suggests Betts took ownership of Frenze in 1861 from his uncle Sheldrake Smith. (This is backed up somewhat by a report mentioning Sheldrake Smith as the owner of Frenze in the Cambridge Independent Press 10 August 1861). Thus the railway couldn’t have opened until sometime after. Yet the problem is Sheldrake Smith continues to be in the news throughout the 1860s. For example 26 November 1864 (Norfolk Chronicle) when several employees of Smith’s were charged with stealing ten bushels of oat. and then 25 April 1865 (Bury and Norwich Post) when a haystack caught fire at Frenze Hall and the local brigade had to attend.

The Waveney Valley Studies (1966) says 1868 is when Betts arrived at Frenze thus the line was opened in 1869. That could well be right for Sheldrake Smith continues to be mentioned in the press until at least November 1868. It has been said June a celebration was held in June 1869 (Diss Express 1951) to mark the first operational stage of the railway as far as Sandy Lane, Diss. The length of track opened was probably somewhere in the region of 300 metres.

Further it seems the Jolly Porter Inn at Diss wasn’t in existence before about 1867, hence the premises’ presence would have dictated where the Scole Railway would meet GER metals as well as the ‘Y’ shaped nature of the good yard area, one of those arms which curved away from the Jolly Porter towards Sandy Lane and Frenze/Scole.

Betts and his vast estates do not make the news pages until the 1870s, so it is quite safe to assume the Scole railway had not been in existence at any time before the late 1860s.

This does sort of tie in with the legal action the Great Eastern and Betts were embroiled in which began in about 1870. Clearly the GER were already grumpy about Betts and his newly built railway and granary barns and warehouses which completed the scene.

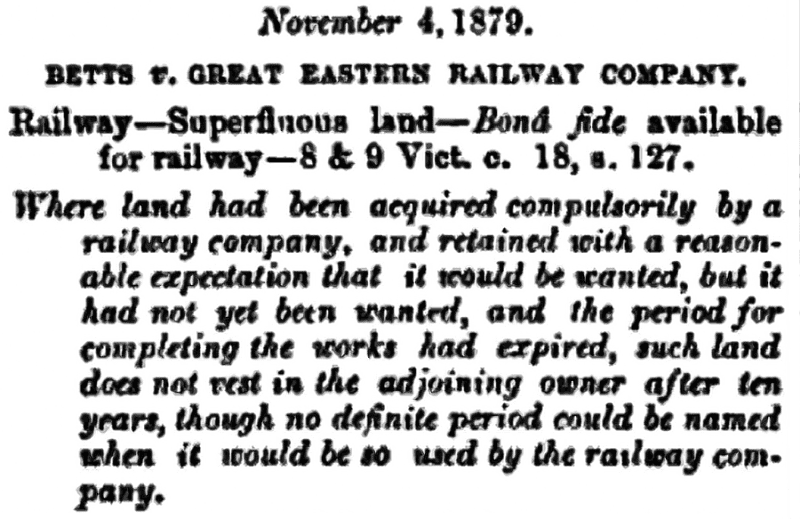

Betts versus the Great Eastern Railway

During the 1870s the Great Eastern Railway (GER) and Betts had a dispute over the use of lands adjoining the railway at Diss, and this was heard in the courts 1873-1879 (Google). The dispute revolved around warehouses and land used by Betts rented from the GER. Various buildings, including granaries and warehouses had been built by Betts and others and this included the beer house (the Jolly Porter Inn). The land consisted of a length of 960 yards (at the most eighty yards in width) sited alongside the main railway at Diss station towards Walcott Green bridge. The GER wanted to build a new access road from the north to supplant that from the south. The GER attempted to take some of the land back and Betts objected. The question was whether the land was superflous or not – in other words the use to which it had been originally intended for had expired, for the GER claimed they wanted the land back for other purposes.

The case in summary. Justice of the Peace Vol 44, P. 232 (1880) Google Books.

There was dispute whether the Jolly Porter ought to be where it was, seeing that it wasn’t really meant to be there, but the fact Betts railway and workers used it and it was adjacent to the railways themselves sort of gave rise to the notion that well, it did serve a particular purpose thus had to be an exception of sorts. Further it was adjacent to a granary that Betts used which too was served by his railway.

The courts decided against and the GER made a lengthy appeal. The courts decreed that if the granary was taken away, Betts would in turn require that something else to replace this because the then existing received a variety of goods by the Scole railway. The judges suggested had the Great Eastern not wanted the lands be used for the purposes they were put to, the company should have put a stop to it quite a few years back. The GER tried to denote that the land was subject to later development as per the railway act however the courts decided the lands were not superfluous – in other words the use they were originally envisaged for had expired. The GER’s appeal was dismissed with costs in November 1879.

Frenze and William Betts from Kelly’s Directory of Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk 1883. Google Books.

Frenze was where William Betts lived. A church could also be found as well as warehouses still extant that are said to have been used by the Scole railway. Nearby is the remains of a bridge over the Waveney, and not too far away are said to be some stepping stones across the same river.

Continued in part two – the railway’s closure and what remains of it.

Leave a Reply