One might have thought Yup its Pompeii! Celebrating Rail 2000 had been written in jest, for there are no railways to be found two thousands years ago – and yet in that article there were a couple of illustrations depicting steam trains within the Pompeii landscape! There’s every possibility people thought this was a joke or I had got my research impossibly wrong – who’d ever have the idea of celebrating railways 2000 years ago for #Railway200! But I wasn’t far off for some weeks later this was indeed the subject of a talk by Gareth Dennis at Hopetown in Darlington (this was initially to be held on 3rd April 2025 but it got cancelled – there’s another on 4th June). The subject of the talks: ‘From Ancient Greece to California – A Longer History of Railways‘.

Yikes! Its ‘Rail 2000’ at what can only be the very heart of #Railway200! Hopetown Darlington.

Within that very article (Yup its Pompeii! Celebrating Rail 2000) there was in fact a tiny hint of seriousness in regards to the Romans and their trackways – for it was they who had employed a widespread use of guided transport systems which were a sort of early railway. Sadly its difficult to determine who exactly had postulated the earliest notion within modern history that the development of the railways stretched much further back into history that was often thought.

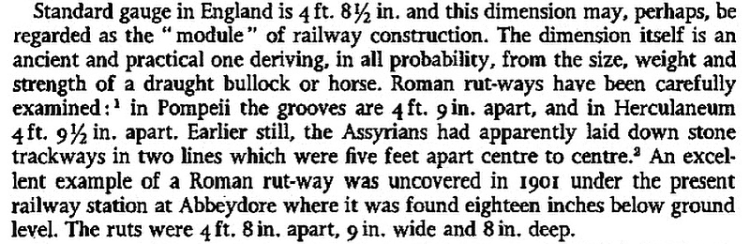

A notable attempt at divulging the idea that railways were anything but a product of the industrial age was Charles Lee. One might know of his work on London’s underground – eight books in all. Or his Early Railways in Surrey, The First Passenger Railway, and also The Welsh Highland and The Penrhyn Railways – just some of the many titles Lee wrote. The earliest in that line of work was a series of papers on the early railways (or guided wheel systems) of the world and he makes much mention of the Romans. This was illustrated in the first of a lengthy series of articles published in the Railway Gazette during 1937. In later articles written during 1941, Lee details how explorers had seen these rutways as no less than being the predecessors of the railway.

It takes a certain resolution to write about things that are suspiciously not what one would deem as constituting a railway. There are those who do however see ancient stone trackways with grooves for the guidance of a cart or a chariot, and how these are indisputably an early predecessor of the modern railway. There’s no doubt Charles Edward Lee was certainly one of those and his work was wide ranging, covering every subject from Roman roads to the first ever histories written on various railways such as the Mumbles and the Metropolitan District among others, not forgetting the London underground lines.

One of his earliest works for the Railway Magazine was a feature on the Southwold Railway, published just a couple of months after that line’s closure in 1929. He was also editor of the Railway Magazine for a number of years – and it is by decree of that stewardship that a considerable number of leading articles on various railway topics were written. His work featured in other railway journals too. For example his substantial work ‘The Evolution of the Railways’ (published 1937) was originally published as a series in the Railway Gazette between April and June 1937. The first instalment of this in regards to the Roman era can be viewed at the Internet Archive.

Some other addenda related to that work was published instead in the Railway Magazine, where Lee details some further findings on those particular Roman Roads that had grooves for guiding the cart wheels. London Rail’s author was quite fortunate to acquire a copy of the February 1941 journal containing this additional work entitled ‘The “Railways” of Ancient Greece’. In this work Lee makes mention of the fact ‘that something comparable with a railway track was used in the days of Tiglath Pileser I, King of Assyria circa 1120-11105 B.C.’, …and ‘probably from the Phoenicians that Greece learned the significance of permanent way and introduced it to Europe’.

Aside from those ancient roads around the Mediterranean, Lee also illustrates similar systems which were discovered in Britain – for example the discovery (or re-discovery in both 1901 and again in 1908) of a Roman Road at Abbeydore railway station in Herefordshire furnished proof these guided wheel systems had too be used in Britain – and the gauge? It was 4ft 8 inches. Charles Lee concludes that after the fall of the Roman Empre this sort of guided waggonway system would not be seen again until around the 15th and 16th centuries – and that is basically when the modern history of the railway pretty much begins.

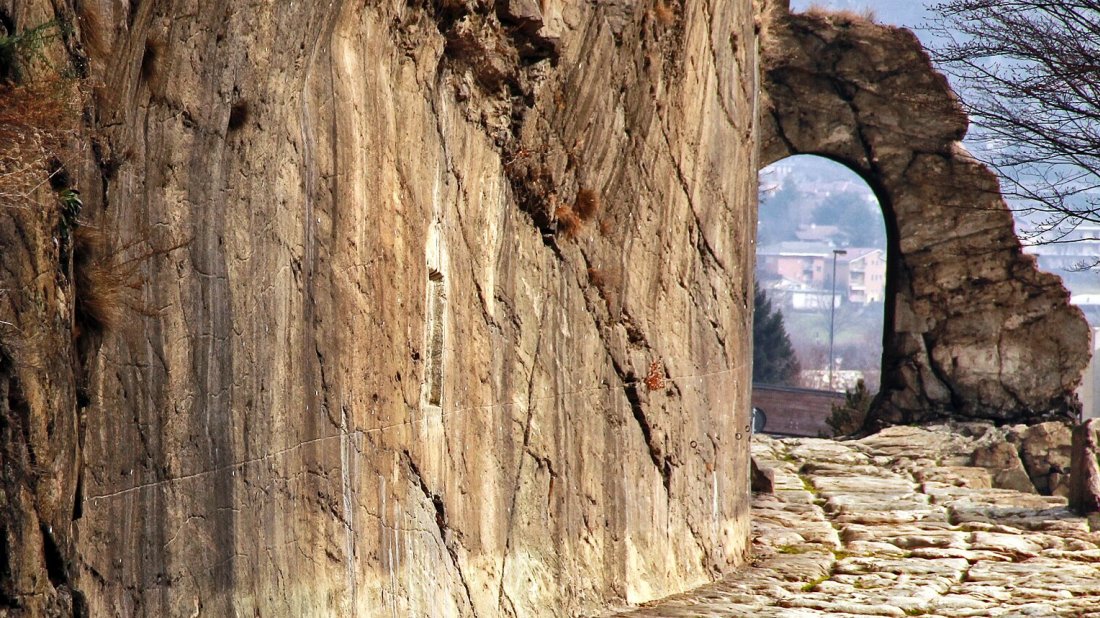

Early example of a wagon road that had cause to erode the centre section of roadway because of the blocks of stones placed at intervals, inadvertently creating what was essentially a guided trackway. The large stones were stepping stones, or essentially in modern terms, pedestrian crossings. Repository.

Lee, in his later works, published a picture of what appears to be a Roman road in Syracuse that was designed to guide waggons perfectly. It was what is known as a perfect example of a rutway (or as some put it, a stone railway) and that was no doubt a very rare find. If its veracity is indeed what it is meant to be, then its an indication the Romans really had honed their notions of what a guided trackway ought to look like. (But read later for doubts on that…) Picture upscaled and colourised by the author from the original in the Railway Magazine for 1941.

The gauge of these trackways according to Lee were 1.44metres (or 4.72 inches) which is interesting because, again, its near the standard gauge of 4′ 8½ inches. In terms of the measurement concerned its said this was taken between the axles, thus the actual track would have been somewhat wider. But there’s every possibility the average width could well have been to the ‘standard gauge’ or thereabouts.

There’s one problem. One could not encounter another wagon coming the other way and not be able to pass it. An old saying which was to ‘have a happy groove’, apparently alluded to the success of being able to pass along these ancient roads and not meet another in the opposite direction. Interestingly, the modern expression to ‘find one’s groove’ (or niche) in life – may have far older origins than is commonly thought.

There is of course the possibility the trackways in Syracuse illustrated by Charles Lee were anything but. In terms of modern knowledge and archaeology, there is suspicion these early ‘railways’ arose due to a different origin rather. They were well formed and certainly constituted an impressive sight – but were probably not designed as a deliberation but rather more one of having been eroded. See this multi part series on the problem of cart ruts in Sicily. In addition that there’s also the mystery of the tracks in Malta – which puzzles even the expert archaeologists – again, even though the average of these were near to ‘standard gauge’ (1.4 metres) they probably were not a design of pure deliberation. This in detail analysis of those tracks in Malta suggests they are partially due to weather and geological conditions, as well as man-made erosion and possibly irrigation.

Malta’s famous ‘Clapham Junction’. This is Misraħ Għar il-Kbir, a site noted for its complex cart ruts. The actual purpose of these is something that’s puzzled many. Wikipedia.

From a personal perspective, these stone trackways are fascinating, but in my opinion there is one huge problem with these. In a straight line (and a fairly shallow depression) they were quite likely fine, and that is understandable when its widely known the Roman roads were absolutely straight. The Romans knew the limitations of their system and that is something that can be accepted in terms of how things had developed. When it comes to curved trackways with junctions and passing places, well, I have my doubts. The more complex these were (plus the ruts getting deeper also) then the greater difficulty it must have been for a cart (or a chariot) to travel along these tracks – and the number of wheels that got broken must have been numerous. Evidently these early ‘railways’ were anything but – with perhaps the exception of true Roman roads.

As railways developed trackage entailed plateways, or extremely thick and deep wooden rails and so on, many of these systems were somewhat ineffective. Its only with the development of the railway since about the 1820s that a long lasting track formation has been enabled and trains could be propelled more easily. Part of the struggle was that old chestnut – how to procure a track that could best manage the weight of a locomotive as well as propel the trains effectively. Blenkinsop and Trevithick were pioneers no doubt, but the track they used and the rail interface was archaic. Even those built by Outram were quite limited too and in a sense all these systems were considerably limited in their application. This is why the development of the modern railway is important. Its not the width of the track or how deep (or how wide the rut is) but rather its the minimal area of contact between the wheel and the rail (or the guide) itself. The modern railway wheel barely touches the surface of the rail, and its this minimal contact that gives modern railway systems the excellent property of having least rolling resistance.

That is not to say there were no serious attempts at what could have easily been the forerunners of a railway system. As the above examples show, in Syracuse and Malta, what look like the forerunners of a railway system, the explanation for these is more obtuse and they are likely not intended as deliberate guided trackway systems. There are notable examples however of pure, deliberate guided trackways and two of those are discussed briefly next.

The earliest type of railway (in an approximate sense) may well be the Nubia trackway in Africa – what is in fact known as the Mirgissa boat road (see this lengthy document from Research Gate). This was a portage system that enabled boats to traverse the Nile to its upper reaches. Much like the Dilkos described next, these were a sort of railway that lent towards the portage of boats past difficult terrain and there’s every certainty the Pharaohs had employed guided trackways from a very early age – this being 1000 years earlier than the Dilkos example. Thus the earliest possible semblances of what could be a railway had existed almost three thousand five hundred years ago!

Its certainly curious the early portage railroads in the US (such as the Allegheny Portage railroad) had adopted a system first employed around three thousand years earlier. The portage railroad was in the modern sense, a means of permitting trade upon a canal or river to continue where certain obstacles such as impossibly hilly terrain or dangerous rapids had stood in the way. One might think the UK never had any such examples of this. However the Blisworth Hill Railway (detailed in London Rail’s first instalment of the Railways and Canal Tunnels series) was in many senses a kind of portage railroad! Not only that, some of the country’s canals had inclined planes (among these the Shropshire tub boat canals, the Grand Western Canal, the Chard Canal and the Bude Canal) and the most advanced of these was the Foxton Inclined Plane – a short lived but stupendous engineering achievement. In every sense all of these were portage railroads too.

Perhaps the best examples of a rutway (besides the Romans) were the Corinthians who had use of what is now known as the Diolkos paved trackway. This is sometimes acknowledged as the father of the railways for it was in essence that. It operated for more than 600 years from its inception up to about fifty years after the death of Christ. Mosaic Projects.

The replacement for the Dilkos came in the form of the famous Corinth canal. Attempts to build this were first begun after the Dilkos railway had ceased operation. However such attempts failed and it was not until the modern era (eg the late 19th Century) that a canal was finally built.

The Dilkos and the Mirgissa were isolated examples, thus its the Romans who basically imported the concept as they travelled from Italy in their ships to other lands in an attempt to conquer the peoples of those lands, including those in Britain. Whether the Romans had actually used guided trackways in Pompeii is open to debate, but there’s enough evidence in the ruins of that city to indicate the Romans had something that was perhaps in its early stages and got more refined as the Roman Empire spread. In terms of how the grooves sat within the stone roadways, its easy to see these as an early form of the modern tramway.

When one sees a tramway that is set in the road, there is no doubt these are certainly a descendant of some these very early tracked roadways. Arguably even guided busways can also be viewed as a descendant too. There’s no surprise that the early waggon ways used depressions for guiding the truck wheels – these were essentially inverted rails. The above example is of the system at the Horsehay works in Telford. Roger Farnworth.

The interesting fact is just how many of these systems lend credence to the notion that the standard gauge of 4′ 8½ inches is universal and its not entirely a whilm of the British. Yes there’s arguments about that but nevertheless its known George Stephenson had known of this ‘standard’ which was used by old waggonways thus used it as the basis for his new railways and for all one knows that could have been derived from even earlier systems. In a sense ‘standard gauge’ is a bit of a mystery since so many ancient trackways (natural and man made) appear to have an approximate gauge which is somewhere near to four foot eight and half inches. But it must be remembered that no matter what, certain patterns and shapes often replicate in many forms, thus its quite understandable there could have been a ‘module’ pertaining to a standard of 4′ 8½ inches.

How the typical British railway and standard gauge could have come about. JSTOR.

There will always be debate as to when railways actually originated. Not only that – when is a railway in fact a railway? Some of it is probably down to what people think as well as historical knowledge and personal preference. Some of the questions upon the origin of the railways are tackled in this article by the Tyne and Wear Museums.

Yup its Pompeii! Celebrating Rail 2000. (Published 27 February 2025)

The title image is from Wikipedia and cropped to show the section of rock face, grooved roadway and rock built bridge – elements of which led to the modern railway. This was done under the Creative Commons Licence where the image could be adapted freely. The title of the original is Tratto della via consolare delle Gallie and the photographer of the work is Maria Grazia Schiapparelli.

Leave a Reply